A while ago I was saying that I wanted to go back and read the early writings about photography in my search for art. I’d become aware that the questions about the relationship between photography and art go all the way back to the very beginnings of our craft. “Craft” because not all photography is art and no one has ever suggested it was.

This task has been more time consuming than I expected. Partially this is due to the volume of writing available on the subject and partially due to the different writing style one hundred and fifty years ago: it is difficult reading. But slowly the landscape has emerged from the mist and certain threads of thought have become apparent. And the story is more complex than I anticipated.

I think I see in these early discussions a good dose of ego, ambition and a simple desire for self importance. But this is a frailty of man regardless of the endeavour and I have seen it in other clubs with other interests. But through this clutter and noise we can see there were those who were genuinely concerned about photography and what it meant.

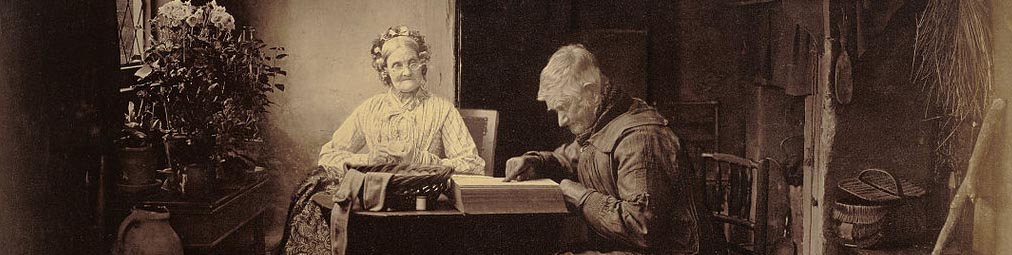

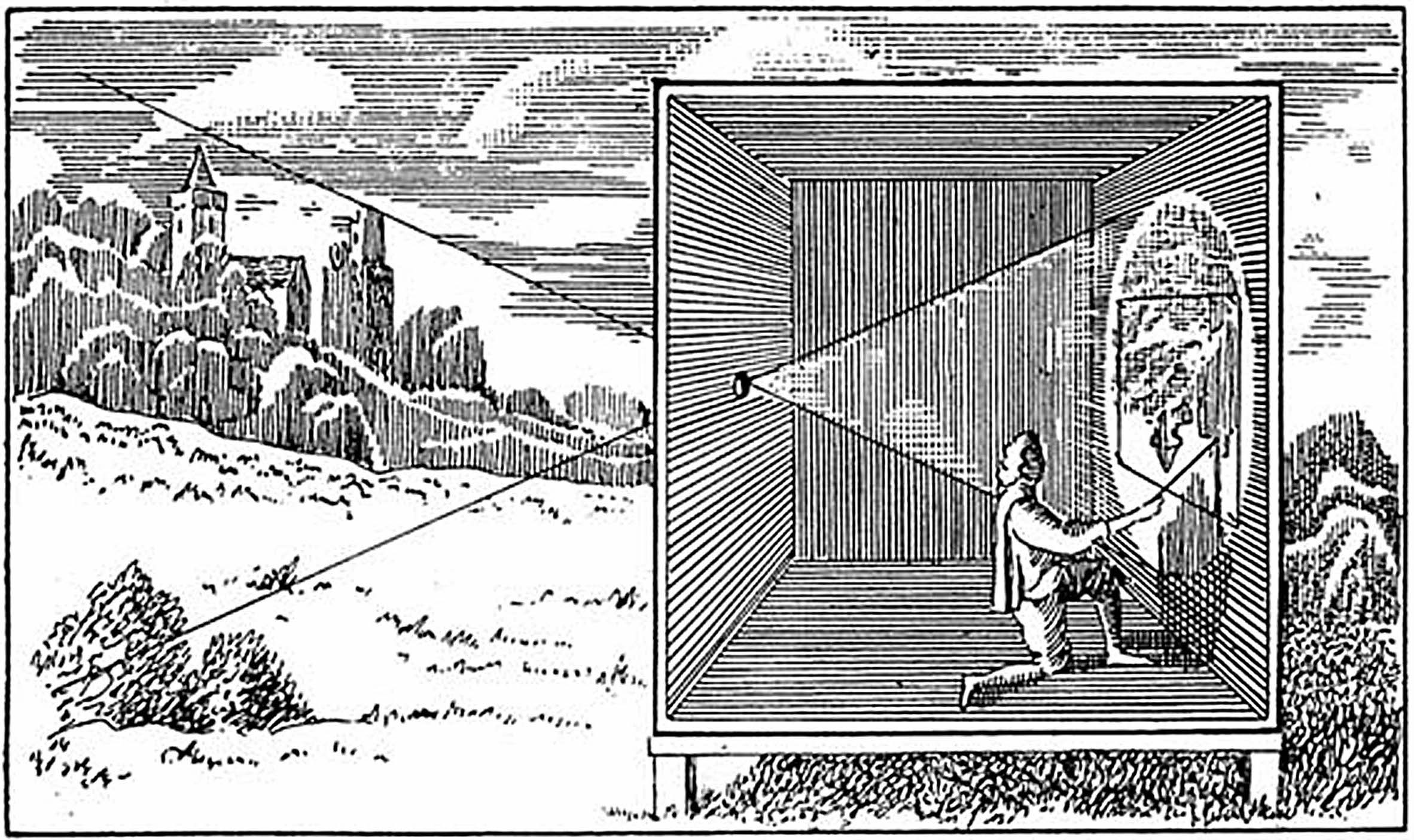

An illustration of the Camera Obscura showing the pin hole and the image cast on the opposite wall. An artist knells before a paper on the wall and traces the image.

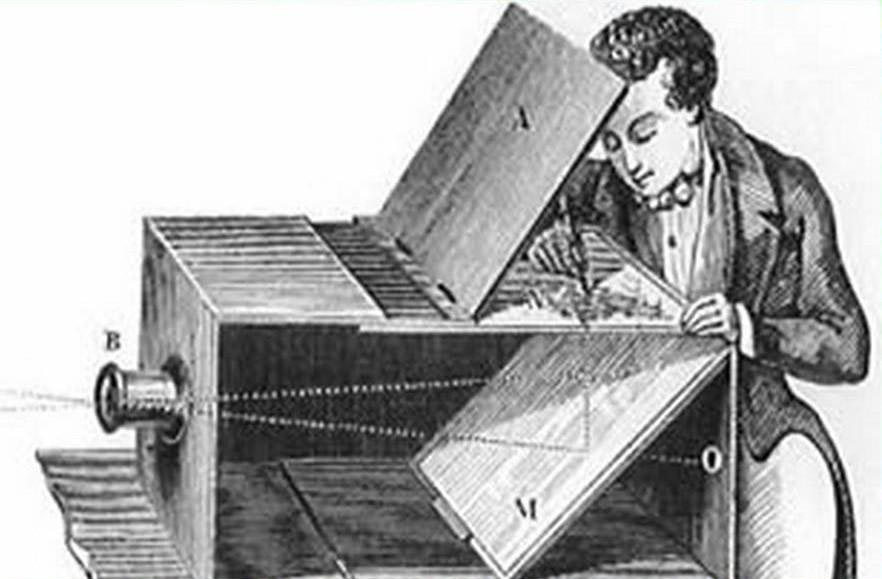

A Box sized Camera Obscura with a mirror projecting the image to the top of the box where it can more easily be traced.

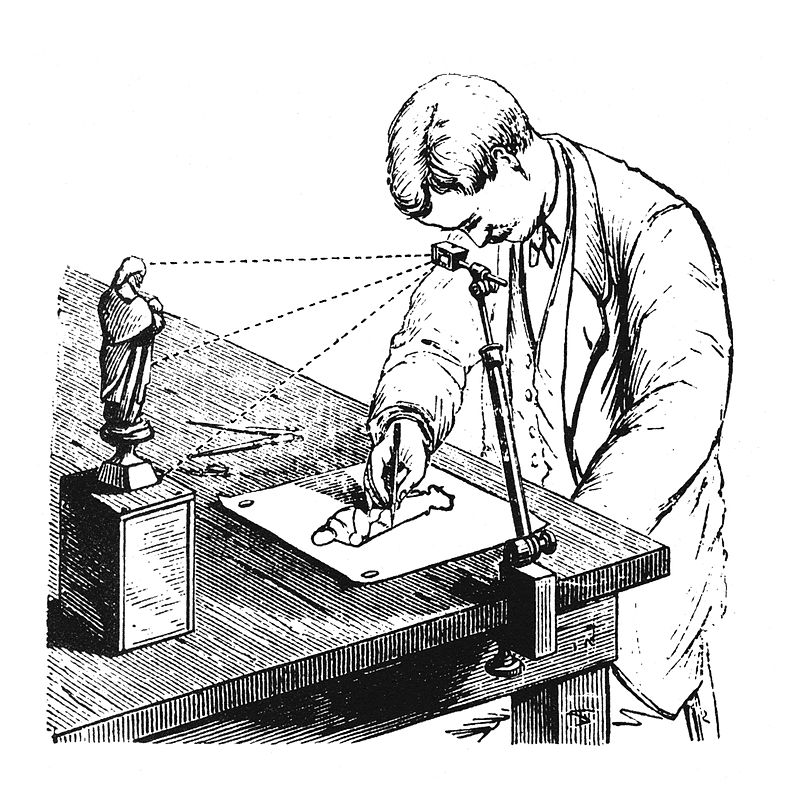

The Camera Lucida is a more convenient device being small and easily portable. However, it can be tricky to use and frustration with it played a role in the development of modern photography, as we shall see.

I have been reading early periodicals. I have already mentioned the “Camera Notes” of the New York Camera Club and Stieglitz’s “Camera Work” and the writings of the “Photo-Sessionsts”. I have since acquired “Camera Craft” magazine issues from 1900 to 1940 from the West Coast. This is all most interesting, but these writings are from around the beginning of the twentieth century. What about earlier? For that I have been reading books on photographic history and rummaging around on the internet.

This exploration of history and photography and art has turned into too much for a single article. I find that when a project is too big to easily comprehend all at once that it helps to break it up into manageable parts. So, I am dividing my thoughts into several sections.

However, do bear in mind that history does not come in sections and all of this was going on at once and there were no clear lines dividing one section from the next. They blended smoothly one into the other. Divisions like I am proposing are artificial and have no place in reality. They are simply devices to aid in comprehension.

How many divisions there will be I don’t know yet because I have not got that far. But I can see the rough outlines of three and possibly four examinations of different thoughts and ideas. I hope my poor writing is enough to bring you along. So lets get to it.

In the beginning photography was an outgrowth of the other graphic arts: painting, drawing, engraving. This may come as a surprise to many but it is true. For hundreds of years it has been known that if you darken a room and then put a pinhole in the window covering you will cast an image of the scene outside on the opposite wall. Try it. It actually works! The larger the hole the brighter image. But, and this is a problem, the bigger the hole the more blur is introduced to the image.

The answer to the blur/brightness problem was the introduction of a lens at the position of the pin hole. The lens allowed you to have a much larger opening without losing sharpness. Now you could project a bright image that maintained its detail. In Italian a room is a “camera” and the adjective for dark is “oscuro”. If we anglicize the words we get “camera obscura” or dark room. So far so good.

If an artist were to pin a paper on the wall opposite the pinhole he could trace the scene with great accuracy and solve the problem of rendering perspective correctly. Of course you cannot drag a whole room around with you and before long artists created a portable box with a lens and a ground glass screen on which to put their drawing paper for tracing. They continued to call it a “camera obscura”. A 45 degree mirror at the end of the box allowed the drawing paper to laid horizontal on the top of the box which was a great aid to drawing. These were in use by artists for a long time before photography. In 1502 Leonard da Vinci describes such a device in Codex Atlanticus. But think about it, the camera obscura was in all respects a camera except there was no place to put film. This was no drawback because these devices were in use centuries before the development of film.

There was another device in use in the seventeen and eighteen hundreds as well, the Camera Lucida. This device used a lens and prism to project the image on the paper. Using this the artists can see the image and the paper at the same time allowing him to trace the image with exact perspective. If you look for “Camera Lucida” on the internet you will find that you can still buy these devices.

When photography came along, this was the technology available. This and chemistry. In an age when many artists were also amateur chemists it was well known that some substances reacted to light and would darken on exposure to it. No one had figured out what to do with this fact but the stage was set.

The Pencil of Nature is considered to be the first book published that was illustrated with photographs. It was published in six parts between 1844 and 1846.and contains 24 examples of Calotypes by Talbot. Even in this early work we can see examples of photography as a record of events and as art. The text is short but well worth reading. This is a message from the birth of photography.

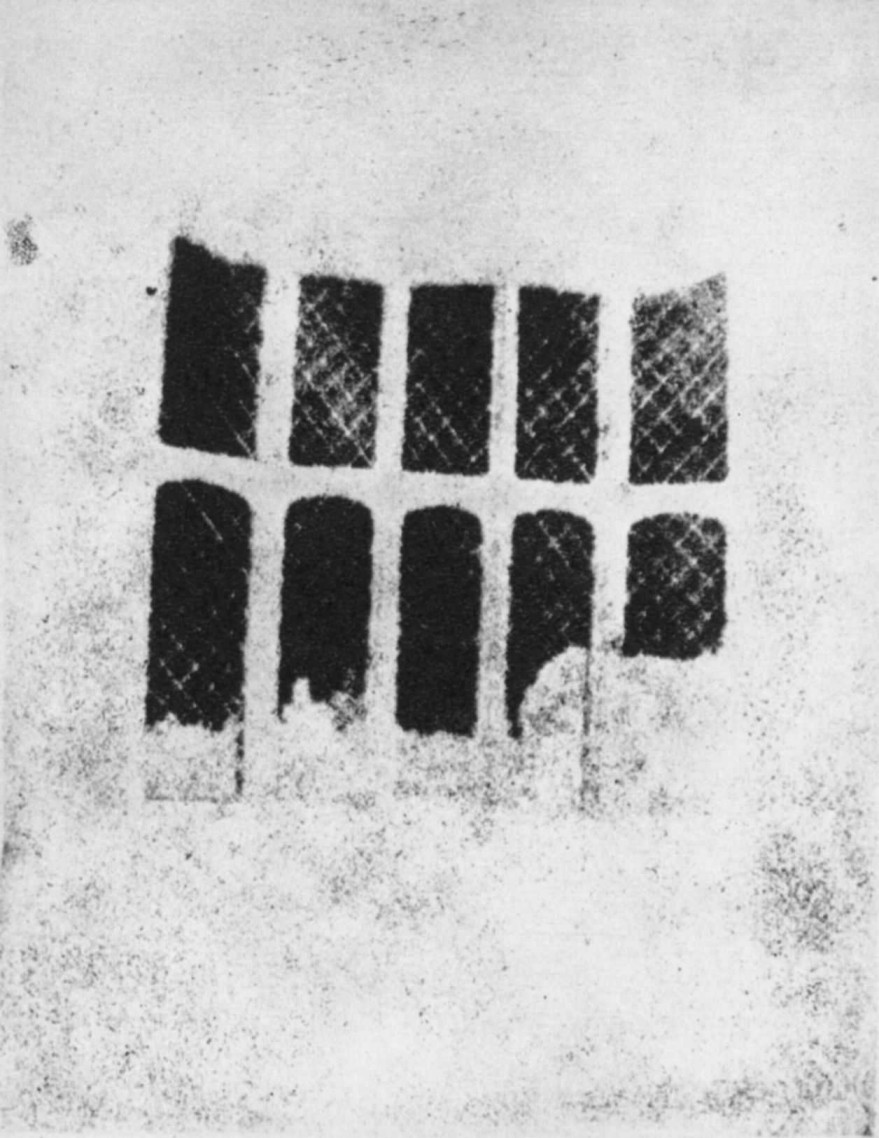

This is a paper negative made by Talbot in August of 1835 of the lattice window in Lacock Abbey, his country home. Wikipedia says this is probably the oldest existing photographic negative image.

However, the daguerreotype, as this process was known, as marvelous as it was viewed at the time, was limited in its scope, difficult and even dangerous to process, and multiple copies of the same image could not be produced. As a result, it was not easily adapted to the needs of artists or the hobbyists of the time. Something more was needed.

In early October of 1833 another would be artist was attempting to use a Camera Lucida on the shores of Lake Como in Italy to create sketches of that wonderful place. But he was having trouble with it and becoming frustrated. We know this because Henry Fox Talbot wrote about this experience in his book, “the Pencil of Nature” published in 1844. As he struggled with his sketch he wondered if there was not some other way to capture his image. He said “It was during these thoughts that the idea occurred to me …. How charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably, and remain fixed upon the paper!”

Talbot was an interesting man. He was elected to the Royal Society in 1831 for his work in optics, chemistry, electricity and integral calculus. When he returned to England from Italy he looked into how to fix images on paper using the camera obscura. He began experiments in early 1834 and by the following year he had some

preliminary images to demonstrate. And it is the process he developed, a process that was to become known as the Calotype, that led the way forward for photography whereas Daguerre’s process proved to be a dead end.

Plate VI from “the Pencil of Nature” entitled “The Open Door”. The caption under the Plate reads as follows: “The chief object of the present work is to place on record some of the early beginnings of a new art, before the period, which we trust is approaching, of its being brought to maturity by the aid of British talent. This is one of the trifling efforts of its infancy, which some partial friends have been kind enough to commend. We have sufficient authority in the Dutch school of art, for taking as subjects of representation scenes of daily and familiar occurrence. A painter’s eye will often be arrested where ordinary people see nothing remarkable. A casual gleam of sunshine, or a shadow thrown across his path, a time-withered oak, or a moss-covered stone may awaken a train of thoughts and feelings, and picturesque imaginings.”

Talbot had come up with a method for making paper negatives that could be printed over and over. And what is more, the process was reasonably simple and the chemicals were not dangerous. It was admirably suited to amateur efforts. Our modern photography was on its way as early as 1835.

The first book illustrated with photographs was printed in 1844 and was Talbot’s own book, “the Pencil of Nature”. In it he fires the first volley in what was to become a raging debate. In the “Brief Historical Sketch of the Invention of the Art” that he prefaces the book with he says in the first line: “It may be proper to preface these specimens of a new Art by a brief account of the circumstances which preceded and led to the discovery of it.” There it is. Photography is art.

The majority of his illustrations are more of a record keeping style and rather dull. However, we can see in Plate VI, shown above, that he is thinking like a painter in setting up his image. He even references the “Dutch School of Art” in the text below the image.

Once the process became simplified and safe, people took up the new craft very quickly. Some were artists and used photography to capture images from which they would paint, or they began portrait businesses, some began documenting the world they saw, and some took pictures of their children and family just like to day I suspect. But very quickly some formed clubs and began organizing showings of their photography and these developed into very sophisticated salons organized as the painters did. Photography aspired to be painting.

Very early on the artists attempted to create photography that looked like paintings. They copied the style and contents of paintings often portraying the sentimental images so popular in the Victorian age.

Once negatives were available, creative photographers began combining two or more negatives into grand images. They posed models in classical ways, they combined them with painterly backgrounds. They tried to create images in the styles already accepted by society as art.

As people with similar interests will do, camera clubs began early. One driving force was the creation of common darkroom facilities for the use of members. We are talking about the 1850’s and 60’s and there were no photo labs to develop your film. That was still several years in the future. So darkrooms were very important and frequently difficult for amateurs to create on their own.

There was an informal group known as the Edinburgh Calotype Club in 1843. 1852 saw the creation of the Leeds Photographic Society and in 1853 a club was formed in London styled the “Photographic Society of London” which quickly received Royal Patronage and eventually became the “Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain”. The stated intent of the Club was to promote “the art and science” of photography.

“When the Day’s Work is Done” is a photograph by Henry Peach Robinson from 1877. It is a combination of 6 posed negatives that have been combined to create a scene in a painterly style celebrating the dignity and strength of simple folk, a common Victorian sentiment.

“Fading Away” is another of Robinson’s works from 1858 created from 5 negatives. Besides being overly sentimental the subject of a dying young girl was considered to morbid for Victorian tastes. But again, it is in a painterly style and an attempt to make photography resemble painting.

Nancy Newhall relates that the first meeting of the “Royal” took place on the 20th of January 1853. Sir William Newton addressed that meeting. He was a well known miniature painter and he made studies of his subjects with photography and painted from the photographs. Many artists used photography this way.

In his comments he complained that the images he was taking were too sharp and that they lost the atmosphere he wanted as a painter. He suggested that the images were improved by setting the lens slightly out of focus “thereby giving a greater breadth of effect and consequently more suggestive of the true character of nature.”

He went on to say that he made this suggestion “because it has been recently stated in this room that a photograph should always remain as represented in the camera, without any attempt to improve it by art. In this I by no means agree, and therefore I am desireous of removing such false and limited views as applying to the artist, or, indeed, to any person having the skill and judgement requisite.”

This caused great consternation at the meeting and subsequently in correspondence which was published in the club’s journal. There was a sharp division between those who wanted to record exactly what the camera saw and those who sought to use the camera to create their vision of reality. And as usual, there are always people who want to tell others the “correct” way of doing things.

Within twenty years of the creation of the craft there were two views of photography: the one was that it was to record what was there and no more and the other was that it was permissible, even desirable, to influence the image to create in the photograph the artists vision by injecting feeling. This could include several techniques from filters in front of the camera lens, to dodging and burning during printing, combining negatives one upon the other, even scratching, painting or writing upon the negative. Anything to advance the photographer’s vision of the scene.

Of the two emerging schools the one that saw photography as an extension of art, of painting, was the dominant view. However, that is not to say that people were not taking all kinds of pictures without regard to these discussions either to earn a living or for personal reasons. Just as today, it was a minority of photographers that cared one way or the other. But they were the ones that wrote the books, wrote the letters, and gave the speeches and so they are the ones that were heard.

One of the champions of photography as art in the 1860’s was Henry Peach Robinson who was an advocate of combination printing and photomontage. He was trained as an artist and actually had some of his work in oils shown at the Royal Academy. However, he was introduced to photography early in his life and devoted himself to it. He took part vociferously in the debates about the place of photography and stood against those who felt that the image should be as the camera produced it and no more. He felt that to create art the photographer had to inject his vision into the work by whatever means he found suitable.

In 1868 he published a milestone work on photography: “Pictorial Effect in Photogaphy” in which he explained the ways of creating an image using combination printing. He asserted that combination photographs were as demanding of the photographer as paintings were of the artist.

He strongly advocated photography as an art form all of his life and wrote and lectured on the subject. In 1870 he was elected Vice-President of the Royal Photographic Society and took part in its proceedings for decades.

The arguments raged on, with the champions of photography as art seeing photography as another means of painting and able to create art in the same vein. I can only imagine what these early protagonists would have thought of Photoshop!

From this period my favorite quote comes again from Sir William Newton at a subsequent meeting of the “Royal” when he again caused an uproar by suggesting “differential focus as a means of interpreting an image, as an artistic control.” The meeting became heated as they argued about the merits or not of his “artistic control”.

Nancy Newhall tells us that during this uproar Newton said he recommended artists use soft focus. But then he said “Photography is a wide field: each may take from photography what he requires; he is not bound or tied to any rule that I know of; let him take his own course, by which not only photography will be advanced but art will be considerably improved.”

This brings us to the mid 1870’s approximately. At this point, those who are interested in where photography fits into the world of art are divided into two camps: those who want images just as the camera sees them and those who want to manipulate images to create art similar to paintings. As an art, photography is still dominated by its graphics arts past and the “photography as art” group are trying to emulate the painters. They are producing images that are composed like paintings and they are showing their work in salons as the painters do. To them photography is “art” in the same way as painting is art.

But in all of this, in this scramble to make photography into “art” we see no definitions or descriptions of what art is. That always seems to be the problem with these discussions: art is a moving target and what is art is different depending upon the age and the commentator. Next time we’ll have a look at what contemporaries of the time thought constituted “art”.

This website is the work of R. Flynn Marr who is solely responsible for its contents which are subject to his claim of copyright. User Manuals, Brochures and Advertising Materials of Canon and other manufacturers available on this site are subject to the copyright claims and are the property of Canon and other manufacturers and they are offered here for personal use only.