I bought a book the other day and, as books will do, it got me to thinking. I shouldn’t buy books. No, no that is not the thought. I got to thinking that I don’t really know what I’m talking about. At my age that is a rather discouraging discovery. But this is what good books are supposed to do, is it not? They are a part of the conversation of life and they draw us in, involve us and give us new perspectives. Well, I got a new perspective and it is that I don’t know what I am talking about.

However, lets go back to the beginning. I came across a used copy of “From Adams to Stieglitz” by Nancy Newhall in one of the bookstores I frequent. The author, although not a well known photographer, traveled in photographic circles and was acquainted with the great American photographers of the early to mid 20th century. She wrote extensively on photography and wrote the text to accompany photographs of Edward Weston and Ansel Adams amongst others. Her husband, Beaumont Newhall, was the curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the author of a very authoritative history of photography, “The History of Photography”. Her work was, and continues to be, well respected.

This book is a collection of her writing and reminiscences of some of the great men of photography. It goes beyond the pictures and into the personalities of these people and talks of the opinions and forces at work within the craft that shaped what we see today as photography. Her prose carries you along and brings her subjects to life.

I had not really thought of it before, but the things I am writing about in this blog, searching for the art in photography, have been discussed and argued about over the last one hundred years and more. And the thing that struck me is that I know very little to nothing of these discussions. How, if I don’t know where the discussion has been, can I carry it forward and add anything new to it?

My new book was made for browsing. The chapters are not long and they each encompass a single individual so it is a book

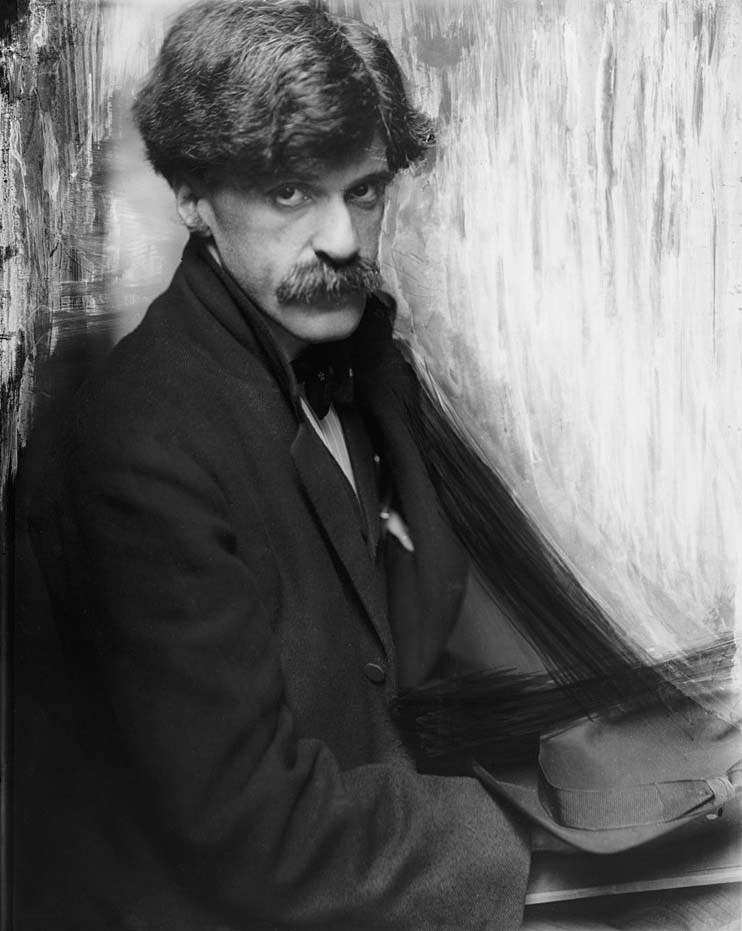

with which one may spend a few minutes here and there to great benefit. I knew the name Alfred Stieglitz from my other reading and so the first chapter I read was about him. I then referred to my other books and the internet and came up with a picture of the man and his place in photography. He was very influential in the early 20th century world of pictures.

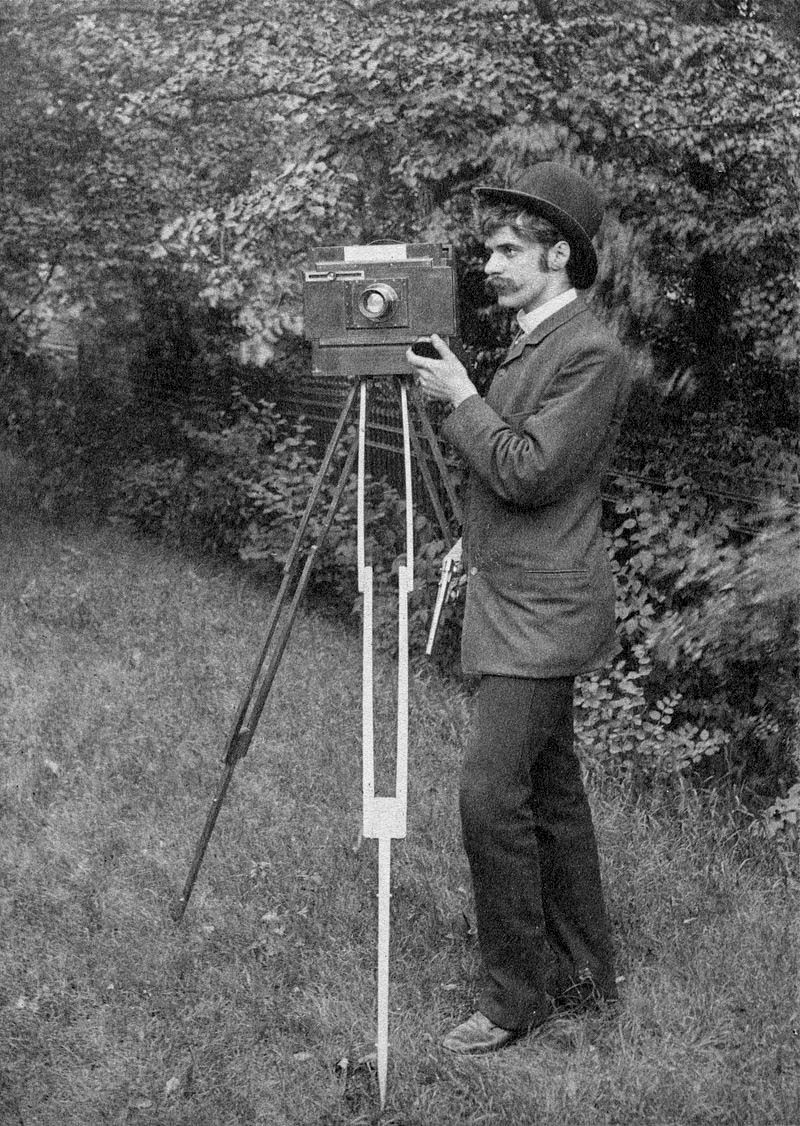

Stieglitz was born in New Jersey January 1st 1864 to German Jewish immigrant parents. In 1881 his father moved the family to Europe believing his children would receive a superior education there. Stieglitz studied in Berlin and while there met German artists who interested him in photography. He bought his first camera while there and traveled with it in Europe taking photographs. Photography became, for him, a passion.

He studied photography on his own and began writing articles on the subject and submitting

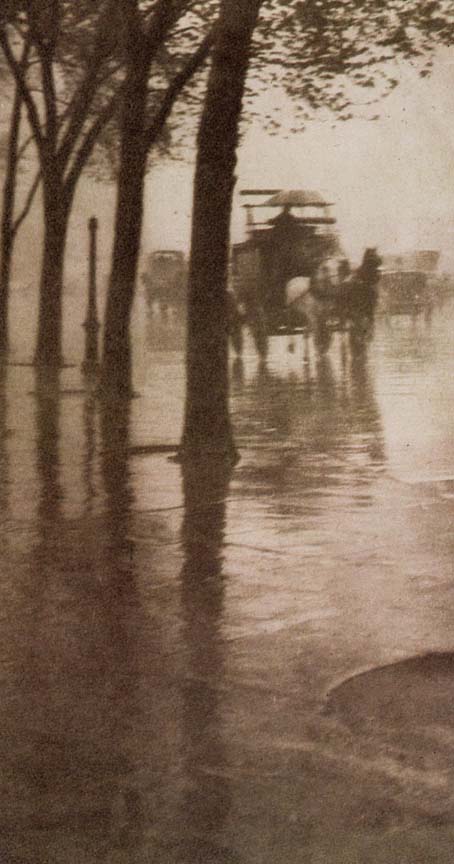

A Wet Day on the Boulevard – Paris – 1897. By any standard Stieglitz was an accomplished photographer but what amazes me is the equipment he had to contend with. Cameras were big and heavy, lenses and emulsions murky and slow. And yet he could produce work like this!

his work to photo competitions in Europe and England. Slowly his reputation began to grow as a writer and photographer. However, he chose to return to the United States in 1890. By this time he considered himself an artist and photography to be an art form.

Back in the United States he continued to take pictures and write and his articles and photographs began to attract attention and critical acclaim. In his writing and speaking he advanced photography as art at a time when serious art galleries and museums did not show photographs or accord them the exalted position of “art”.

This discussion had been raging in Europe for 30 years about photography as an art form. Once cameras passed from the realm of interesting novelty to mainstream craft photography’s position as an art form became a subject for debate amongst graphic artists and photographers. Stieglitz became embroiled in the debate while in Europe and brought his feelings on the subject to America where he ultimately had great influence.

Steiglitz was a proponent of natural photography, the camera showing what the eye sees. And yet, I see more than that. In the four pictures above I think he has captured what the heart felt.

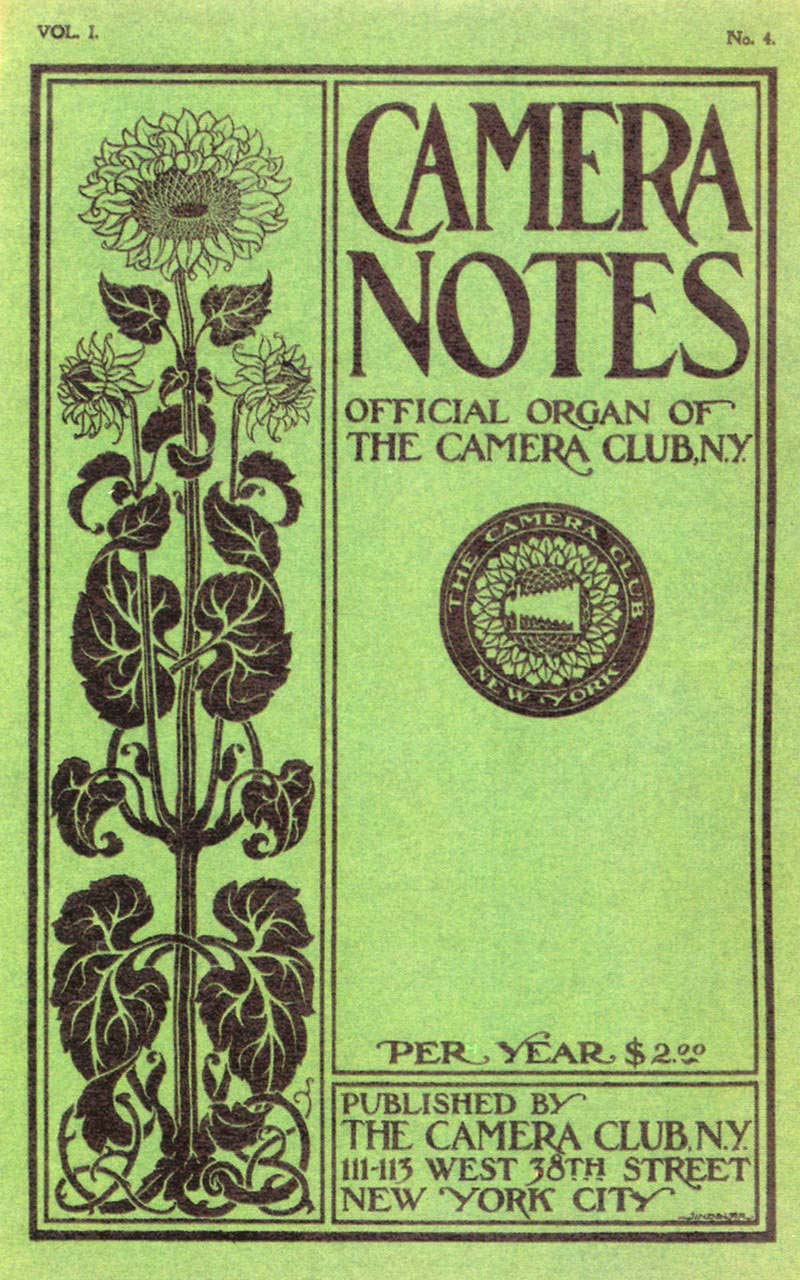

Camera Notes was the photography newsletter of the New York Camera Club which magazine Stiegliz turned into an authoritative voice in America for photography as art.

Camera Work is available to us, every issue, thanks to the efforts of the University of Heidelburg in Germany and I recommend this collection to you. It is well worth an evenings browsing and reading.

In 1895 there were two main camera clubs in New York City. Stieglitz spent that year working on the amalgamation of the two clubs and in May of 1896 they became the Camera Club of New York. He turned the club’s newsletter into a photographic periodical called the “Camera Notes” over which he exercised full editorial control. For four years he used this forum to advocate for photography as art through articles, editorials and photographs. For display in the magazine he selected from what he considered were the best works of his day and reproduce them. And he continued to exhibit his own work in Europe and throughout America.

Stieglitz was a powerful force with strong opinions and a sometimes not diplomatic manner. Clubs being what they are, there were those who resented his control of the Camera Notes and his influence in the club and a power struggle ensued.

A group of photographers gathered around Stieglitz and urged him to strike out on his own. By 1902 he had resigned from the Camera Notes magazine and set out to create his own quarterly publication which he called the “Camera Work”. The group of friends who came with him he chose to call the Photo-Secessionists presumably because they were leaving the style and philosophy of the photographers in the New York club.

The first issue of Camera Notes came out in December of 1902 and publication continued into 1917. The quality of the photographs and the writing soon made this the premier photography publication in the United Sates and, again, Stieglitz used it as a vehicle to advance photography as art. The pages of the Camera Work are full of the photographic issues of the day.

In November of 1905 he opened his first gallery on 5th Avenue in New York which he called the “Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession”. This had to close briefly a few years later for want of cash but it reopened in 1908 as Gallery “291”, being located at 291 5th Avenue.

In this and his subsequent galleries he began to show modern graphic art along side photography and he began introducing modern artists of Europe to America feeling that the juxtaposition of photography and modern art would engender discussion which would benefit both disciplines.

By 1920 traditional art galleries were approaching Stieglitz to exhibit his work and to stage his own shows. Finally, in 1927, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts acquired 27 of his photographs. This was the first time a major museum included photographs in its permanent collection.

He continued to show his work, to promote other photographers and artists, to arrange shows and exhibitions until his death in 1946. In his lifetime he presided over the acceptance of photography as a valid art form and labored tirelessly to see that come about.

This is a very short introduction to Stieglitz if you have not known of him before. I recommend the Wikipedia article about his life to you for more information. A web search will reveal many more photographs by him.

So, getting back to my original point, here was a man who pushed his whole life for photography to be a recognized art form and yet I know little of his writing. And in this he was not alone. There was an ongoing discussion that began in the 1850’s about photography as art and if it

Gallery 291 was a modest affair and the photographs were displayed in the tradional format for the day, and often for our day as well: small and matted on 16×20 boards. It seems to me hard for photographs to compete with art when the prints fall so far short of the great colorful canvases on display in the art galleries and museums.

was not art what was it. This conversation, argument really because it became very heated, arose once photography came out of the novelty stage and became a mainstream craft taken up by anyone interested. It was carried on in the photo journals and newsletters of the day and because it was in print much of it is available to us today.

This is the gap in my education of which I have become aware. I need to know how this conversation went and how it turned out. This is especially true if I am to hold forth on the subject in my own little blog.

But where to start? Looking on the internet I am surprised at how much material there is available to read. It is truly like a web where every name leads down a new path with page after page of information.

But you have to start somewhere. So I am going to start with this new book by Nancy Newhall and I will let it lead me where ever it will. And I will make my notes right here where you can follow, if you so wish.

The second track I intend to follow is the “Camera Work” magazine itself. I have found that the University of Heidleberg in Germany has posted a facsimile of every issue on line and I intend to read them all. Follow the link above and you can take

One last image by Stieglitz: Grand Central Terminal – 1929. Beside being an advocate for photography, he was a great photographer!

this journey with me. I have already looked through a few of the early issues of Camera Work. They are interesting reading and the photography is wonderful. The ethereal quality of some of this early work is striking. I have no idea how one would recreate it with modern cameras. I can see that I am going to enjoy this exercise. And maybe in this process I will find out what “art” is and whether photography can be “art”. And maybe my pronouncements on the subject will carry a little more weight and maturity. I would like that.