When I wrote “But is it Art (Part 1)” it was my intention to examine the struggle of photography to be recognized as a legitimate art form and in the process have a look at what constitutes Art. That is a big subject and I was going to make it a series of two or three posts

However, as I tried to get into this second installment and start delving into the concepts of Pictorialism and Naturalism in photography I got lost. It took me several tries before I understood my mental block and how to resolve it. And I will explain all of that.

However, in this process I began asking myself why write this at all? Is it really that important to understand this now remote history? I think we should look at that question first before getting back to the search for the Art in Photography.

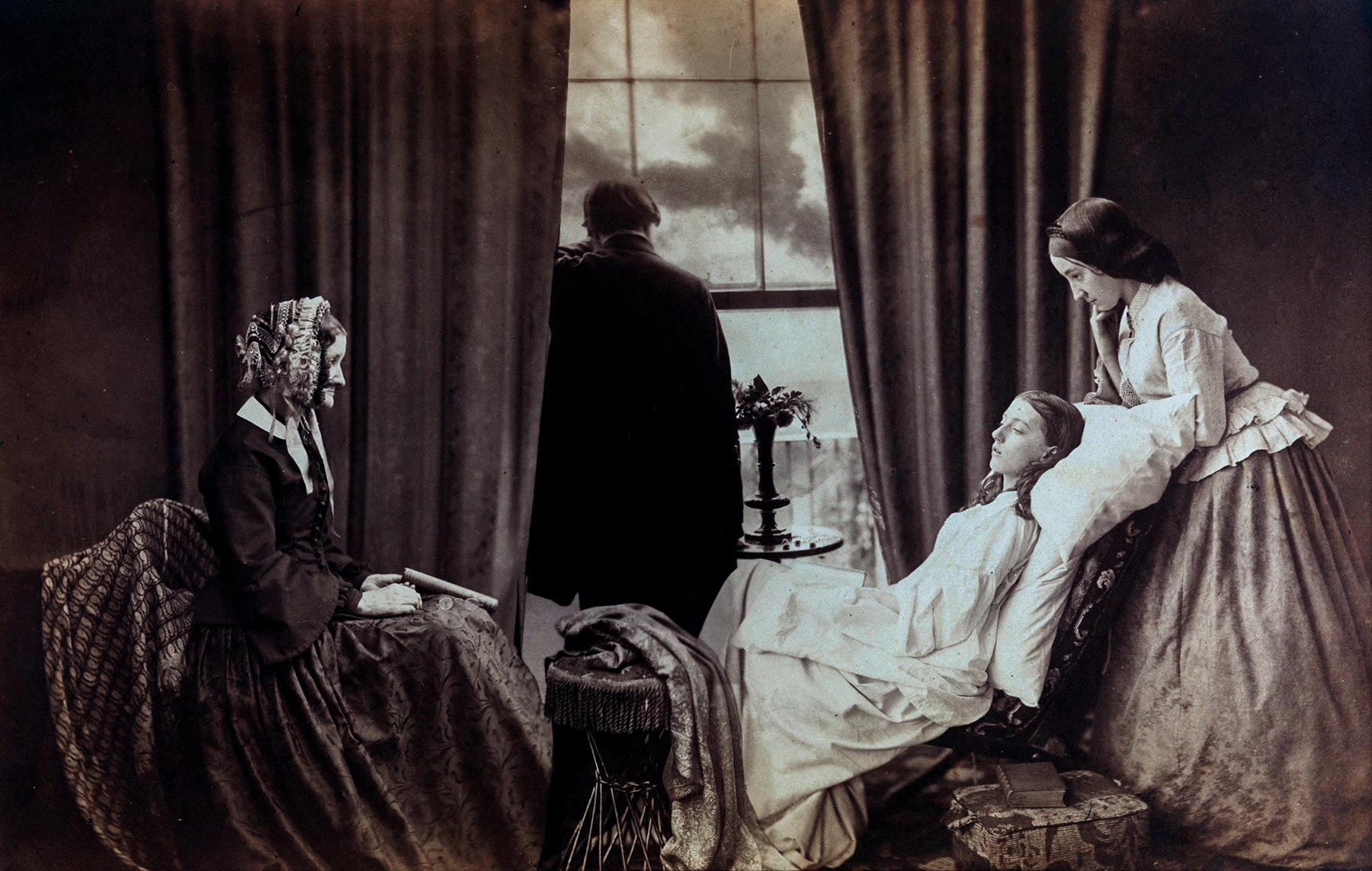

This picture, “Fading Away”, by Henry Peach Robinson is from 1858. It was controversial in its day as being too intimate and morbid for public viewing. It shows a young girl dying of tuberculosis while her family gathers around her. But it is a perfect example of “Pictorial” photography. The image is carefully posed, the layout is in the style of paintings of the day, it is extremely sentimental as Victorians were, and the image is a composite of five negatives. It looks artificially contrived.

There are many, maybe most, photographers who pursue their craft without a thought for how this came to be or what photography means in the modern world. And then there are those who do care. For me, the answer lies in the words of Ansel Adams when he said that “You bring to the act of photography all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have heard, the people you have loved”. I think he meant that your life’s experiences and interests create a sensitivity in you that is expressed through your photography.

When I look at a scene and consider its photographic possibilities and I have taken the time to learn of the masters of the past, looked at their pictures, considered what they thought about the camera and its images, I think I take a better image. I have tried to absorb the images of Julia Margaret Cameron, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Dorothea Lange, Paul Strand and innumerable others. I know which of their images I like and their styles have blended into my own over the years. When I press that shutter I am trying to capture an image that expresses me. And what am I if not the sum of my knowledge and experiences. And if I create art it will flow from that richness of being and knowing.

For this reason I believe it to be important to know where photography has been so I can see where I want to take it.

So let’s get back to our search for the Art in photography. As I said, my original idea was to examine the major influences of various early schools of thought. And I was having trouble defining what was meant when people talked about Naturalism or Pictorialism. And as I ruminated on this problem I came to see that I was hung up on the labels.

Photography has never been neatly divided into this or that so that you could study areas individually. The development of photography has been a surging boiling cauldron of innovation, technology, and passion that blend and flow and labels just don’t work. It is possible to see divisions of thought, popularization of this method or that, but they were all going on at once. The labels are like trees that get in the way when you want to photograph the forest. One man may embrace more than one idea or method in his work, or he may ignore the popular ideas of his time and go his own way.

Into this mix we have to recognize those who would tell the rest of us the right and wrong way to take pictures. I am sure there is a special place in Hades for them. And there are those, the critics, that seek to build themselves up by tearing down the work of others. And these people have written volumes on what one should do and should not do and what is acceptable and what is not. And these are still with us today doing their best to stifle talent and discourage the beginner.

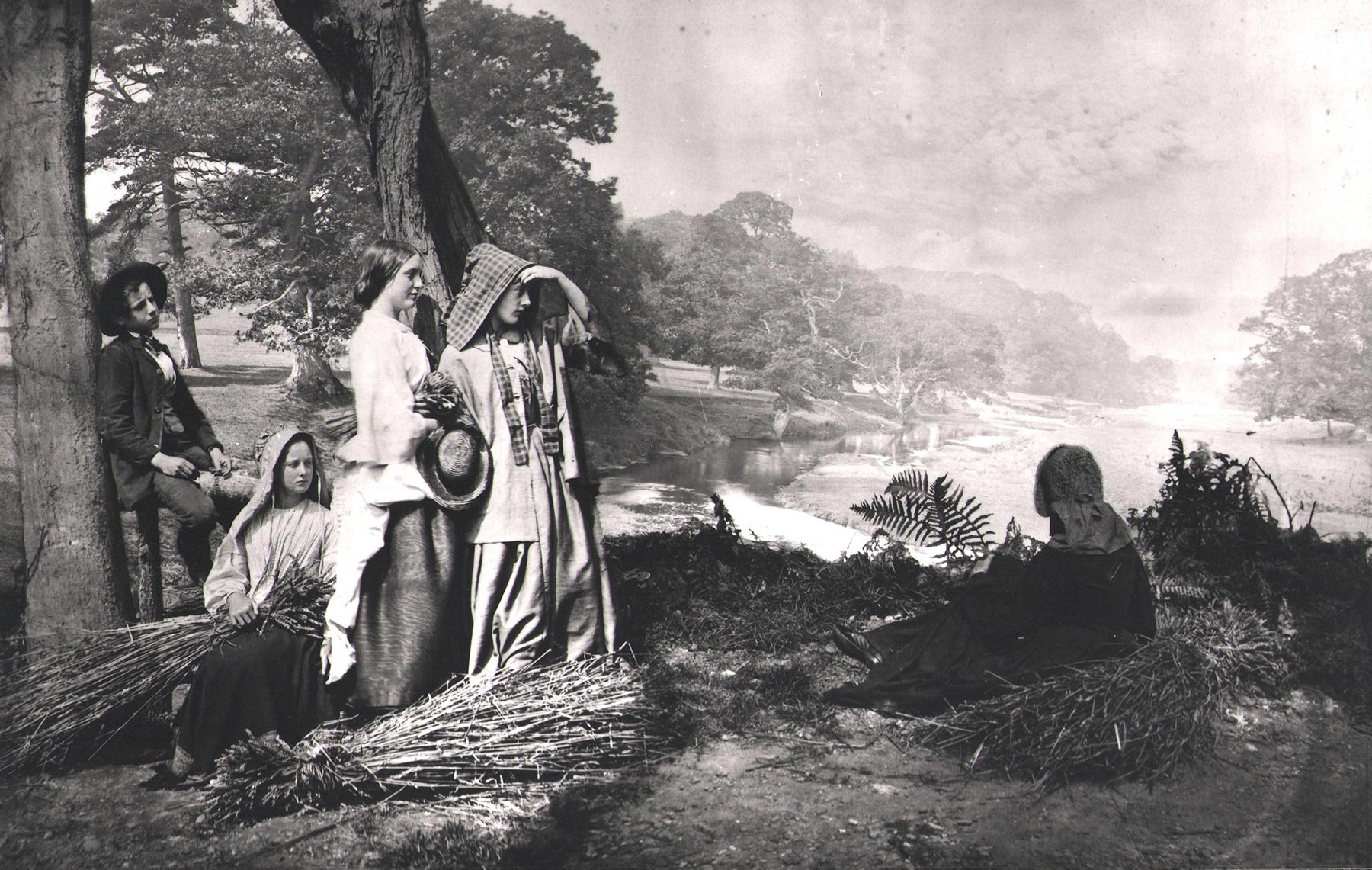

Another photograph by H.P. Robinson from 1864 titled “Autumn”. This is another example of “Pictorialism”. This is an obvious indoor setup in front of a painted canvas background with the figures posed in front of it with various props such as the bundles of reeds, the plants and the ferns. The boy and the seated girl on the left don’t seem to belong and they are probably added from additional negatives. Notice, again, the sentimental poses laid out as if done in a painting of the day.

So let’s see what we can learn from this jumble of history and human nature. You will recall that we were discussing whether a photograph could be Art and if a photographer could be termed an Artist. Photography has many facets: it serves to record information, to identify people, to advance scientific research, to decorate and to entertain. We are not discussing any of those uses of photography. We are seeking Art.

The basic problem with that quest is that we are very fuzzy in our concept of what constitutes Art. We cannot define it but we all feel we can recognize it when we see it. That feeling is too subjective if there is to be a thing called Art. But what does the photographer have to do to be an artist?

Jerzy Kosinski, an American novelist, said that “The purpose of art is not to portray, but to evoke.” In other words, art must stir something in us; evoke a feeling. Edgar Degas, French impressionist painter, said that “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see”. The painter Paul Klee put it this way: “Art does not reproduce what we see. It makes us see.”. “An artist is not paid for his labour but for his vision” said James Whistler.

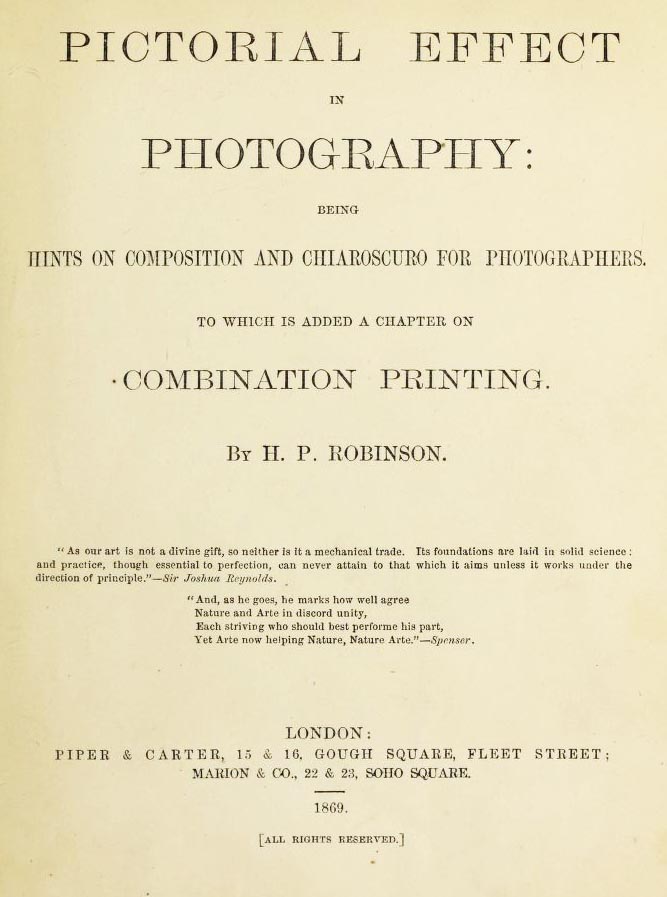

Henry Peach Robinson wrote this very influential book in 1869, about thirty five years after the invention of photography. Read a few pages of this work and see how far we have come since then.

From all of this we can make out an outline of what is Art. It is something that makes us see things that we may not have seen before. It must go beyond mere representation and evoke some inner feeling that moves us. As Henri Cartier-Bresson said “It is an illusion that photos are made with the camera …. They are made with the eye, heart and head.”

If you can’t feel what you are looking at then you’re never going to get others to feel anything when they look at your pictures. Art evokes feelings and summons memories, sometimes recalled from long ago, sometimes subliminal, not recalled but lingering beneath the surface and giving rise to ripples in our consciousness.

The craft of photography began about 1835 with Daguerre and Fox Talbot and for the first 10 or so years it was reserved for the tinkerer. It was a novelty that charmed and inspired but its future impact was only dimly seen. It was difficult, required complex knowledge and equipment, and it was so new that there was no training or photographic products available. You were on your own!

Then, for the next fifty years, it blossomed and slowly gave rise to serious photographers who wanted to create Art. The art these early photographers knew was oil painting and so to create Art people thought the photograph should look like an oil painting. There was a rush to imitate the painters and, in doing this, to pose images, to create effects with multiple negatives, to use props and backdrops, to stage the image all in an effort to create Art. And possibly worst of all, to imitate the sickly sweet overly sentimentality in Victorian paintings of the day. Simply put, if oil paintings are Art then to be Art a photograph must look like an oil painting.

A proponent of this style was Henry Peach Robinson who’s influential book “Pictorial Effect in Photography” published in 1868 was considered for several years to be the authoritative work on photography.

Taking a word from Robinson’s book title, this was “Pictorial” photography. But a backlash developed to this contrived form with various photographers urging that a photograph must represent what the lens saw, plain, unadorned, straight from the camera.

A champion of this new movement was Peter Henry Emerson who argued strongly that the photograph should be a true representation of what the eye, and camera, saw. He wrote about his theories of photography and art in his 1889 book “Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art” which was to influence photography for the rest of the century. And of course this style of picture taking came to be called “Naturalistic” photography.

I wish we had time and space to look at pictures from the 1800’s and discuss the people who created them and the equipment they used. Some of their work was incredibly beautiful and I can only wish to do as well, even with all of the modern tools I have. Maybe another time we will just look at pictures together.

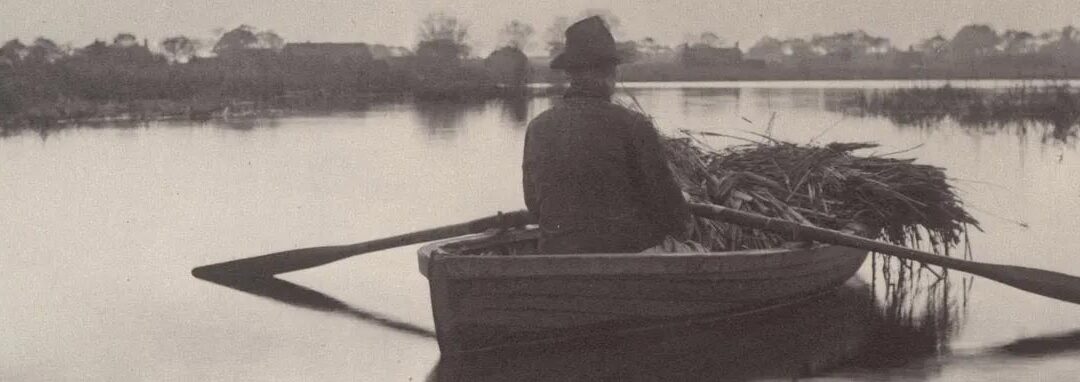

Emerson actually became very well known in his time for his photographic studies of country folk and rural living in England. He published several collections of his works which were unretouched images straight from his camera. He very much proved that the camera could create deeply moving images without the help of cutting, pasting, posing and manipulation.

These two schools of thought were not distinct and we cannot say where one ended and the other began. They blended together and slowly evolved from one to the

other but neither ever really died out. And if you read early writing about photography, say for instance in the journal published by Steiglitz called “Camera Work” you will find that even in the early twentieth century these ideas were swirling around. The reason I was having trouble writing this Part was that I was looking for dividing lines, sharp time periods, a clear transition point. None of these things exist. Where I sought definition there was a blur.

And what of the photography in the last half of the 19th century? Like now, most work was mediocre artistically but some was truly excellent. There were hobbyists who just liked cameras and taking pictures and their work, like now, was pleasant but unremarkable.

And then there were men and women who sought to create Art and they were totally successful as the examples I have included here will attest. Examine them and absorb what the photographers did to create such compelling images. Their cameras were big and bulky, the processes they used were extremely limited, film stock they made themselves or, if they bought it, was of variable speed and quality. And yet they could produce Art.

There is so much to discuss here and it is frustrating to pass over iso quickly. The equipment the early photographers used is fascinating. The chemical processes they had to go through to produce a print is incredible. To be a photographer you had to be a chemist. The two books, by Emerson and Robinson, I have presented here will describe for you a different world altogether in which today’s photographers would be totally lost.

In Part Three of this ongoing Post we will move into the twentieth century and the beginnings of modern photography and continue our search for the Art in photography.

“At Plough, The End of the Furrow”, from Emerson’s photographic album Pictures From Life in Field And Fen (1887). I find this to be a powerful image that contains all of the elements that make up Naturalistic Photography; the image is straight from the camera, shows what the camera saw, and yet tells a story, is pleasing to look at and draws the eye to it.

As a final word for this post, lets look at some words of P.H. Emerson from his book “Naturalistic Photography”. He broke his volume into three Books and in Chapter IV of the third Book he gives some “Hints on Art”. We can find the following words of wisdom there.

“Be true to yourself and individuality will show itself in your work”

“The value of a picture is not proportionate to the trouble and expense it costs to obtain it, but to the poetry that it contains.”

“It is not the apparatus that does the work, but the man who yields it.”

“…when a critic has nothing to tell you save that your pictures are not sharp, be certain he is not very sharp and knows nothing at all about it.

“Art is not to be found by touring to Egypt, China or Peru; if you cannot find it at your own door, you will never find it.”

This website is the work of R. Flynn Marr who is solely responsible for its contents which are subject to his claim of copyright. User Manuals, Brochures and Advertising Materials of Canon and other manufacturers available on this site are subject to the copyright claims and are the property of Canon and other manufacturers and they are offered here for personal use only.