Pictorialism

by Flynn | Dec 26, 2023

In our post “But is it Art (Part II)” we were discussing two early schools of thought about photography: Pictorialism and Naturalism. Both terms are actually difficult to define closely and looking at pictures it can be difficult to place them in one camp or the other. But, when discussing pictures, words can often be insufficient. So let’s look at these two lines of photographic thought through photographs. We will start with Pictorialism and see if we can pin down what we mean by the term.

The creators of photography in the 1850’s and 60’s wanted their new method of expression to be considered as a legitimate vehicle of artistic expression. And they quickly began to push the new medium in every direction. They combined negatives, they played with focus, they experimented with all sorts of print mediums, all in an effort to create Art. They felt that it was not only acceptable but necessary to manipulate their images after exposure in the camera to achieve the image they saw in their mind. This manipulation was new in the 1860’s and eventually drew a strong backlash but it is accepted now as normal in this day of post processing and Photoshop.

But why do we want to look back at these old images? To become an excellent photographer one must look at images in all styles. Only in this way will you find what you like, and what you don’t, so that you can take pictures in your own style. As we look at examples of Pictorial photography we become better photographers and we learn the language of photography so that we can talk intelligently about the subject.

Oscar Gustav Rejlander was a pioneering Victorian photographer born in 1813 and dying in London in 1875. He was an early proponent of Pictorial photography and was adept at photomontage, the technique of combining different negatives to create one image.

On the left is his image “Two Ways of Life” in which an aged teacher or philosopher is introducing two young men to the world. The one on the right is drawn to a life of study, discipline and proper Victorian morality. The one on the left is drawn to vice and dissolution. It is said that this image is composed of thirty two different negatives.

“Two ways of Life” was extremely popular when it was

shown, so much so that Queen Victoria is said to have purchased a copy of this picture as a gift for Prince Albert. It exhibits all the signs of a Pictorial image. Firstly, it manipulates the negatives by cutting and pasting them together. Secondly, it is composed to look like a classical painting of the day. And, finally, it preaches Victorian morality which today would be considered a little overdone.

Do I like it? No I do not. The style and the sentiment seems dated now. The word “corny” comes to mind. But considering it was made in 1857, about twenty years after the birth of photography, it is an amazing accomplishment.

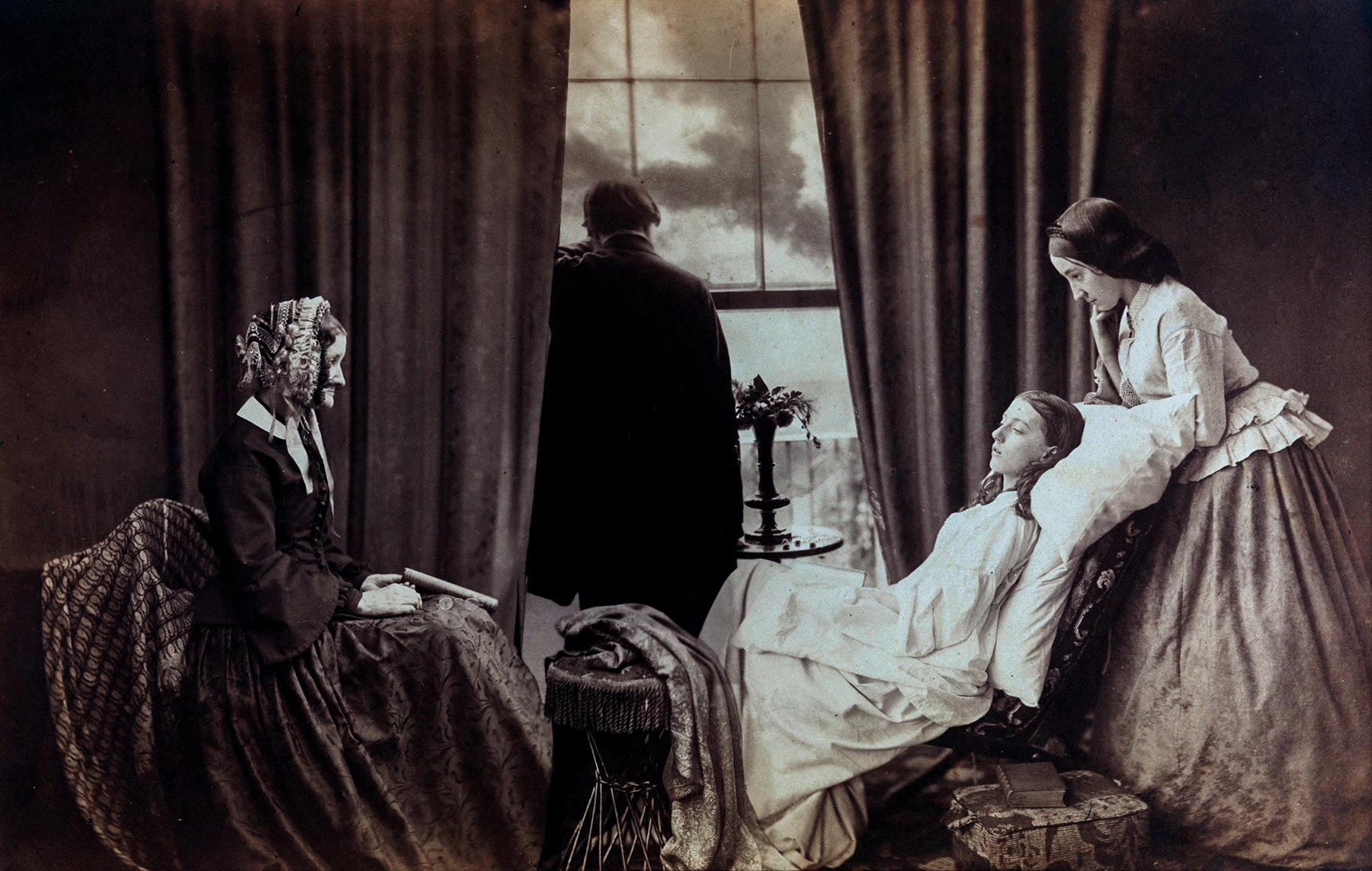

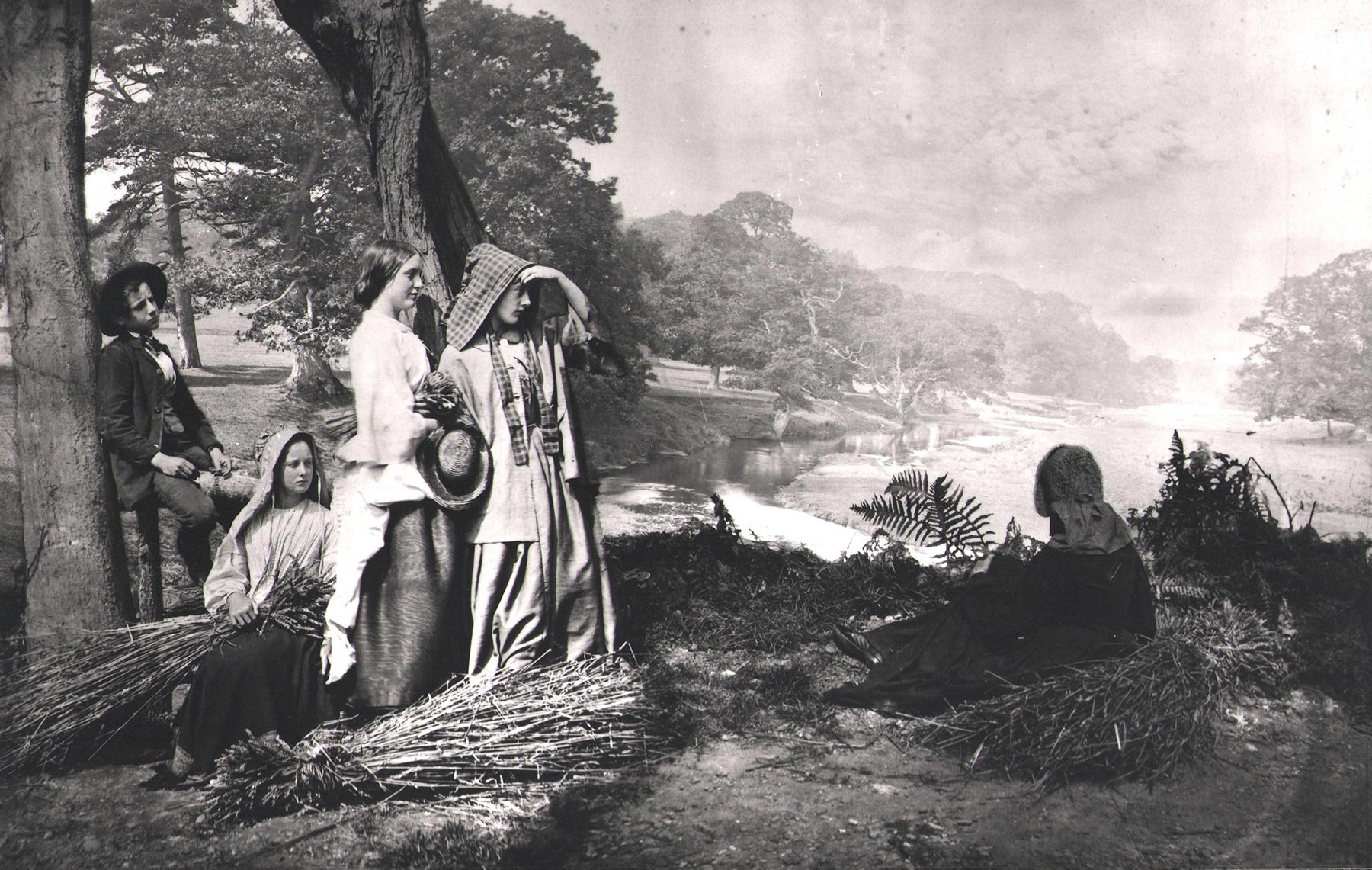

The most visible proponent of Pictorialism was Henery Peach Robinson and the very name of this type of photography was lifted from the title of his book “Pictorial Effect in Photography” published in 1868. Above are two of his images which we shall consider in turn.

“Fading Away” caused considerable consternation when it was displayed. In the image a young woman is dying of tuberculosis with her family gathered around her. The scene was considered too painful for public display. Seven negatives were combined to create this image and despite the excessive sentimentality it helped propel Robinson to the position of England’s preeminent photographer and leading proponent of Pictorialism.

“Autumn” is another photograph by Robinson showing another technique of Pictorialism, stage props. The background in this image is obviously painted. In the foreground are bundles of branches added as part of the scene. The picture is obviously posed to look like a classical painting. Again, for me, this picture is too much. It looks made up and the figures look artificial. However, the images above are early and extreme examples of Pictorialism.

Julia Margaret Cameron was an interesting photographer. Born in 1815 she led the normal life of a Victorian wife and mother until she was around 48 when she took up photography. She became famous for her portraits and images of characters from history. Her output of around 900 known images were taken in a relatively short period of 12 years before her death in 1879.

In her photograph “Whisper of the Muse” she posed musician George Frederick Watts, a personal friend of her’s, as a musician receiving inspiration from his Muse.

This is a classic Pictorial image but it is actually pleasing. It is a studio posed make believe scene that exudes Victorian sentimentality. But still it is a pleasing composition and, for the period, technically excellent. I actually quite like it.

As Pictorialism matured, the pictures got better and some of the extreme techniques once used became less dominant and the images more pleasing.

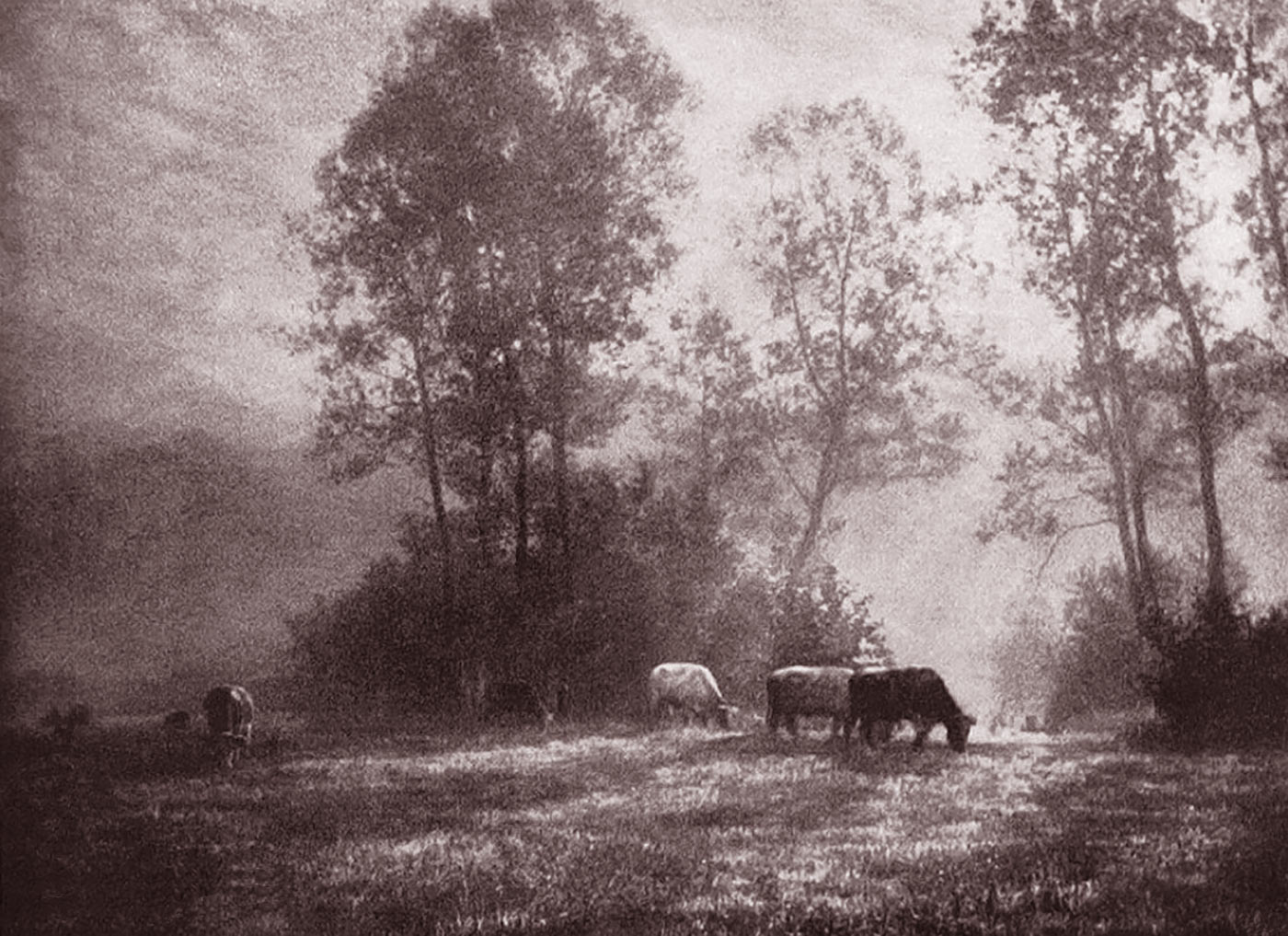

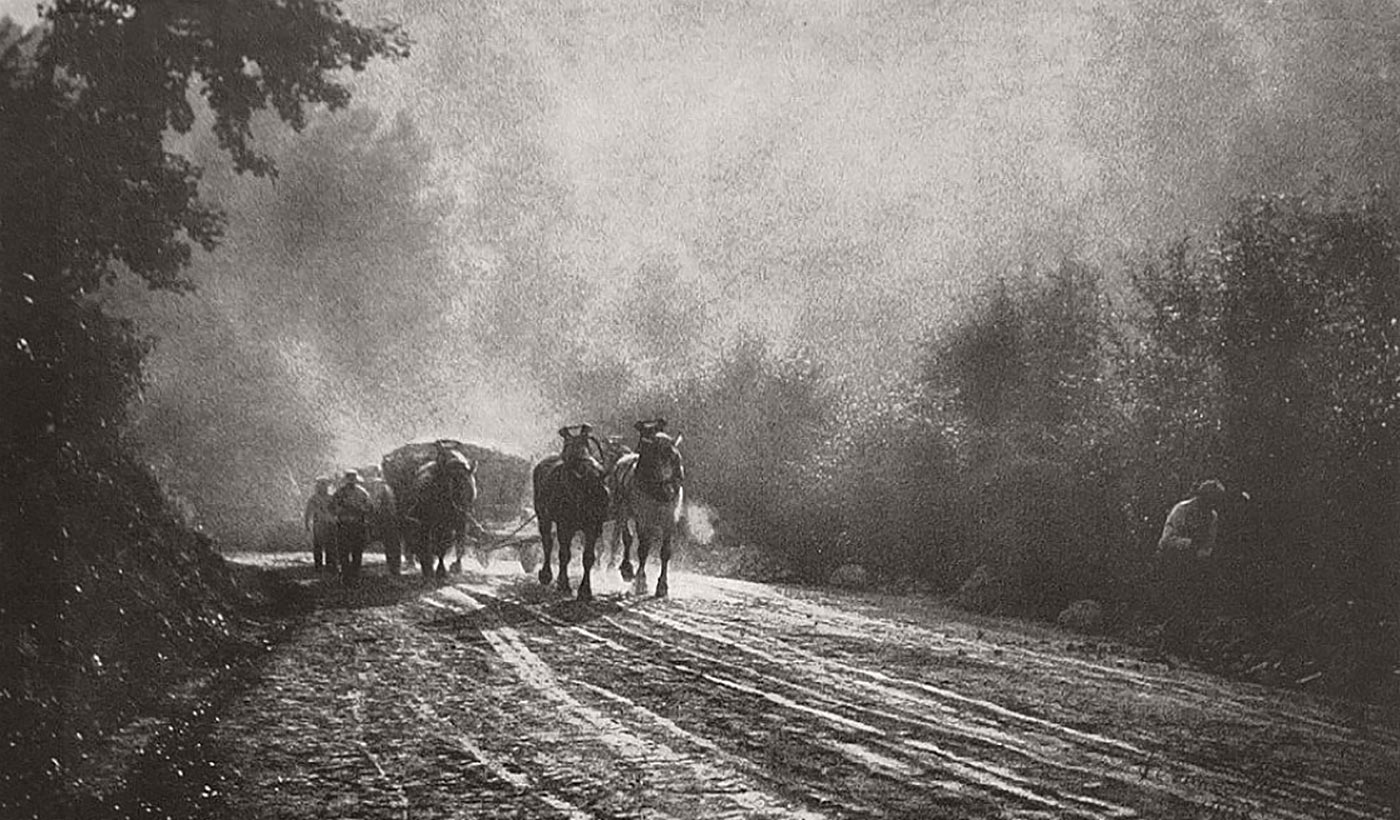

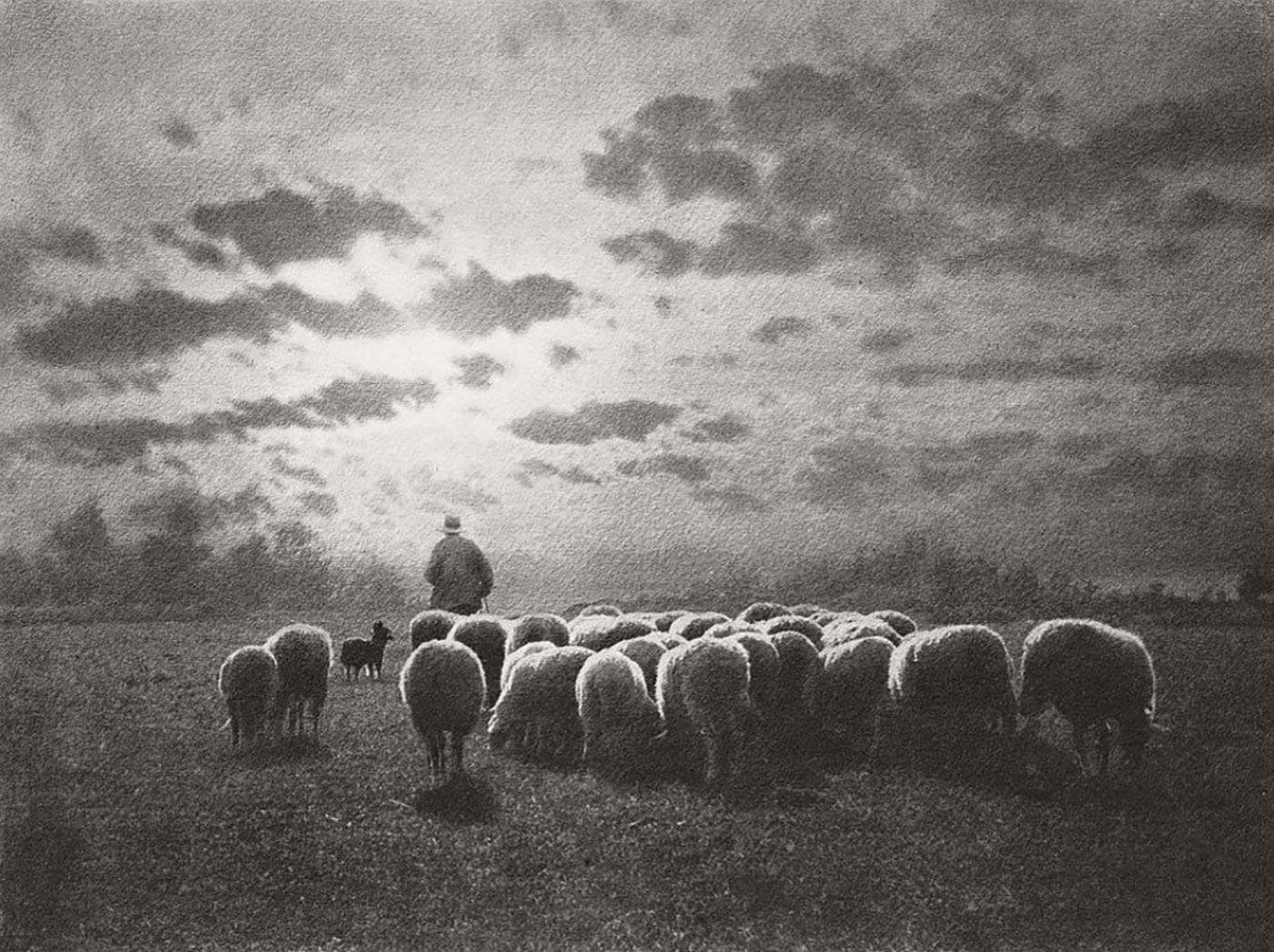

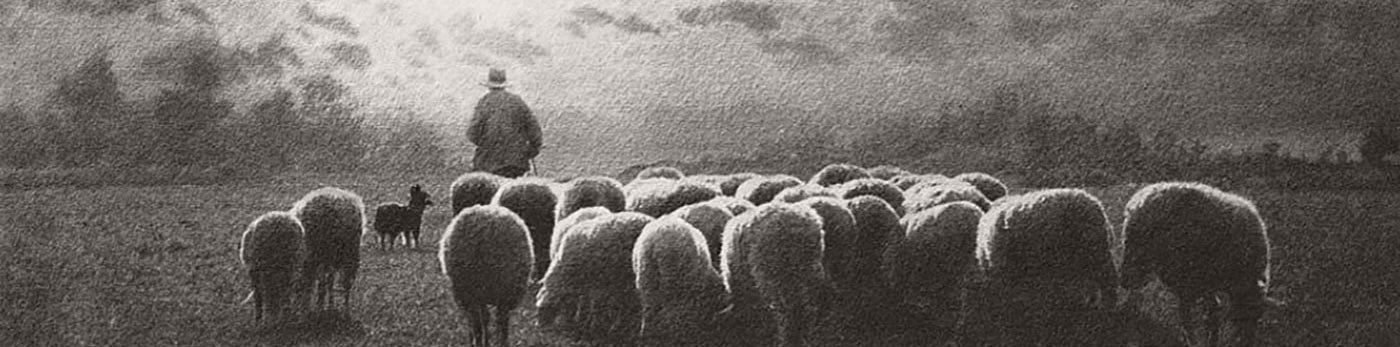

In researching this post I came across a photographer I had never heard of but whom I think is marvelous. Léonard Misonne was born in 1870 and was a Belgian photographer who distinguished himself in his use of light and shadow in his scenic images. His photographic career lasted from about 1896 until his death in 1943.

There are many images on the internet attributed to Misonne. Generally the quality of online images is such that it is difficult to

tell how sharp the originals were or how much grain was visible. And many were not named or dated so we have to go on faith as to their true authorship. However, looking at the style, it is easy to see that they are likely by the same photographer. All of the images below are attributed to Léonard Misonne.

The three images above exhibit the typical traits of Pictorial photographs. Firstly they are very painterly. They look like Victorian paintings in their composition and style of rendering. The top image is backlit giving a glowing diffuse background to the cattle which are rendered largely in silhouette. The bottom left picture has a very dramatic sky which dominates the image. This is a trademark of Misonne and Pictorialism generally. The image on the bottom right, like the one on the left, has a road wet with rain that leads the eye into the picture. They all have been developed in such a way as to convey a delicate halo effect in the trees. They look almost like steel engravings.

In both “A Parasol and a Stroll” and “By the Mill” Misonne uses a strong backlight and misty background. In fact the haze over the background renders it indistinct and seemingly out of focus. Both these images are composed like paintings and with the addition of brushstrokes and color could be credible paintings. And they are both sentimental in the Victorian fashion.

Look at this image above. To me this is truly powerful. The strong diagonal lines in the clouds and the trees are striking. How this was captured one has to wonder. The focus is slightly off, the sky has strong storm clouds, the details seem more like they are engraved rather than photographed. It simply does not look like a photograph. It looks like a painting. I have no idea how the detail was rendered like this but I want to learn. One could spend years studying Photoshop trying to learn how this man did this at the beginning of the last century with lenses, film, chemicals and paper.

Misonne is surprisingly consistent in these works. In this image we again see mist, a strong sky, a soft focus background and backlighting. And again, the image looks like a painting.

I think the work of Misonne reaches the ideal of what Pictorialism was all about. The works seem based on old principals but applied so beautifully that they almost seem modern and could be mistaken for pictures by Emerson and the Naturalists. However, the reliance on less than sharp focus, mist and fog, backlighting, composition and Victorian sentimentality defines these images as Pictorial.

Take the time to search for images by Misonne on the internet. There are lots of them and they are beautiful. There is so much to learn in them. There were many fine Pictorial photographers in the period 1860 to 1910 and they produced wonderful work. And when you consider the primitive state of photography then, the slow lenses, low film speed, bulky cameras, and mysterious chemistry one sees the miracle these pictures represent.

I look at these images and I want to produce prints that look like this. But at the moment, I do not know how. This is the value of looking at the photography of others. I see something I want to learn how to do. And I will one day and when I do I will add it to my repertoire, my style. And that, taken together with other things I have found that I like, will uniquely define my photographic style.

When we put labels on ideas we give the impression that there are sharp boundaries to the thing when that is not the case at all. The ideas behind Pictorialism grew over several years and that growth did not slow even during the height of the Pictorialist period. Ideas matured as the equipment got better and more and more people became involved in photography. Some, like Misonne, carried Pictorialism into the 20th century while others found their photographic thinking changing in the 1880’s. There were no sharp boundaries in this. It was a continuum.

By 1889 Peter Henry Emerson had published his book “Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art” in which he documented the next major movement in photographic style: Naturalism. But even Emerson continued to take pictures that contained elements of Pictorialism. So telling one school of photography from another based on one or two pictures is far from easy and even impossible. One must think of trends and influences and not of absolutes.

To illustrate my point, above are two images of rail yards. One is by Misonne, an avowed Pictorialist. The other is by Alfred Steiglitz who is anything but a Pictorialist. He was the photographer that led America into the 20th century and towards realism in photography. But without some research can you tell me which is which? My point exactly!

These definitions are real and their effects can be felt across the decades into our own time. Here I am wishing I could take pictures like this. But my lenses are too sharp. They capture too much. And this was a complaint made in the 19th century by the Pictorialists. And now and then you see someone denouncing an image processed in Photoshop as “not true photography”. This was a cry heard in the 19th century in the backlash to Pictorialism. So these old arguments are with us still. And to see our way in the modern discussions of photography we should be aware of our photographic past.

One last image by Misonne. I love this man’s work. To me this is Art …. the kind I would like on the wall in my livingroom. I don’t know why it speaks to me. But something in my history draws me to images any Victorian would be comfortable with. His composition is always perfect, the treatment of lights and darks is brilliant. And the amazing thing is that lens sharpness seems irrelevant. So much for all the discussion in photo forums about which lens gives the sharpest images. If you can’t take good images with a Brownie Hawkeye, you are not much of a photographer.

This website is the work of R. Flynn Marr who is solely responsible for its contents which are subject to his claim of copyright. User Manuals, Brochures and Advertising Materials of Canon and other manufacturers available on this site are subject to the copyright claims and are the property of Canon and other manufacturers and they are offered here for personal use only.