In Canon’s possession is the only known example of a Kwanon camera to have survived. It bears more than a passing resemblance to the Leica Model II which was the source of its inspiration.

Canon Begins

Japan was no stranger to cameras. The first recorded camera in the country was a daguerreotype model imported into the Port of Nagasaki from a Dutch ship in 1848. This was during the time when Japan was a closed society and trade with foreigners was prohibited but Dutch ships were allowed limited access to trade into the Port of Nagasaki. However, the winds of change were blowing.

By 1862 there was a photo studio opened in Nagasaki by Ueno

Hikoma and a second the same year in Noge which would become part of Yokohama by Shimooka Renjo. There soon followed other studios and as Japan opened to the world cameras and related equipment flowed in.

In the 1880’s dry plates became common and amateur photography became popular much as it had done in Europe and North America. Just as in other countries camera clubs formed very quickly and photo magazines followed.

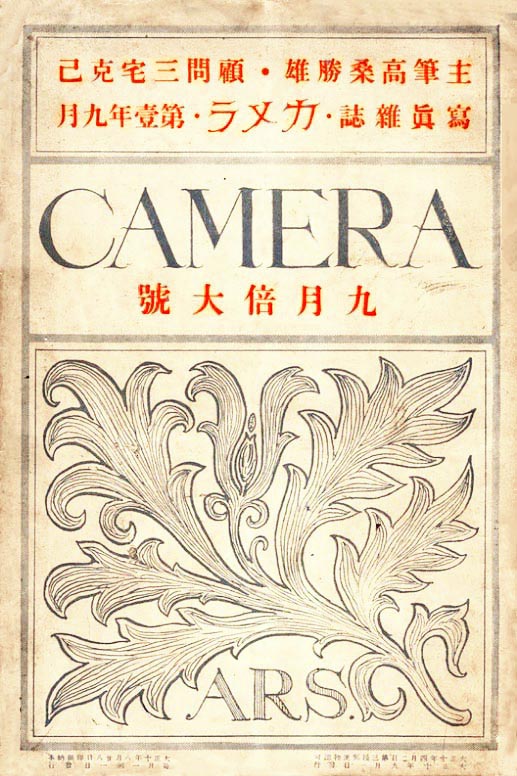

In April of 1921 “ARS Camera” magazine published its first issue and continued into the 1950’s with a brief hiatus during the war years. April 1926 saw the first issue of Asahi Camera magazine which was begun by a local camera club and would become the longest running photography publication in Japan, publishing monthly, except for a period during the war and post war reconstruction. The magazine finally ceased publication with the July 2020 edition citing falling readership, lower advertising revenue and the difficulties occasioned by the corona virus.

The camera market in the 1930’s was well represented with Japanese cameras of all types. However, as elsewhere, they were mainly simple affairs priced for the average person. Of course there were higher end professional cameras but they were plate cameras or large roll film cameras and they were too expensive for the average person.

There were 35mm cameras available but they were not high end devices. At the top of the wish list of Japanese photographers were the German Leica II’s

Goro Yoshida 1900-1993

and Contax I’s. But these were a dream that was out of reach of the average Japanese photo enthusiast. And there was no home grown camera that could compare.

The history of cameras is littered with stories of men who loved to tinker, to take things apart to see how they worked, who liked photography and wanted to build a camera of their own. Leica’s Oskar Barnack was such a man.

In Japan Goro Yoshida was such a man. He was born in 1900 in Hiroshima, yes, that Hiroshima, and as a young man in the 1920’s in Tokyo he apprenticed to a company repairing motion picture cameras and projectors. It was natural therefor that he began to tinker with cameras and think about building one of his own.

It is important in considering this early history to bear in mind that the real facts were not accurately recorded in the first place and they have been filtered through faulty memory and several tumultuous war years. However, we can see the general outlines of events.

The Canon Museum says that Yoshida had the opportunity to take a Leica II apart to see how it functioned. In later years he would say “I just disassembled the camera without any specific plan, but simply to take a look at each part. I found there were no special items, like diamonds, inside the camera. The parts were made from brass, aluminum, iron and rubber. I was surprised that when these inexpensive materials were put together into a camera, it demanded an exorbitant price. This made me angry”

It occurred to him that it should be possible to build a quality camera along the lines of the Leica that the average Japanese could afford. He spoke with his brother-in-law, Saburo Uchida about it and he too thought it a good idea. Uchida had an associate whom he brought in on the project, Takeo Maeda. Maeda would be with Canon in 1974 when he was made president where he would serve for the rest of his life. Later they would bring in Tomitaru Kaneko who would become the first factory manager and chief engineer.

Together in November of 1933 they created an organization, the Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory, Seiki Kogaku Kenkyujo, to develop a 35mm rangefinder camera. They took a room in which to work in the Takekawaya Building, located in a suburb of Tokyo.

Yoshida got to work immediately on a rangefinder camera based roughly on the Leica II. They decided to call it the Kwanon after the Buddhist goddess of mercy.

Exactly how many Kwanon cameras were made is not known. Yoshida was to say that he made 10 initial Kwanons but if he did we are not certain if any of those survived. The facts surrounding this period are very sketchy at best. Canon has a Kwanon they acquired in 1950 which was apparently sold to a private purchaser in 1937. Dechert discusses this camera and refers to it as the Kwanon-X. This is the camera illustrated above at the top of this page. But it is unknown if it was one of these ten cameras referred to or was a later camera built from surplus parts.

Advertisement for Kwanon camera that appeared in a 1934 issue of Asahi Camera magazine. Notice the front mounted film advance knob and the lack of rewind knob. Dechert suggests this is a Kwanon-D.

The Canon Museum refers to another Kwanon which is referred to as the Kwanon-D but they say it was not made by Yoshida and that its origins are unknown. It was apparently a copy of the Leica II. That probably means it did not have the front mounted film advance knob.

Dechert refers to four variations on the Kwanon, referred to as Kwanon-A thru Kwanon-D. As none of these appears to exist now their existence is inferred from advertisements and photographs from that time. It appears that the Kwanon went through various configurations as the design was refined but we don’t know in what order these made their appearance. In one advertisement from a 1934 Asahi Camera magazine the Kwanon appears to have the film advance knob on the front of the camera like the Contax I. There is no rewind knob because the film travelled from canister to canister and did not have to be rewound. There were two opening keys on the bottom which also closed the film canisters to protect the film.

Dechert says that none of these cameras have survived with the possible exception of the Kwanon-X in Canon’s possession. Note that that camera has a film advance and rewind knob on the top deck just as the Leica II has. Therefor it seems likely that this is the last model prior to the end of Kwanon development.

Now, to muddy the waters further, there was an auction of a purported Kwanon-D in Boston on the 29th July 1006 and it apparently sold for $138,000 USD. This is reported by the website Klassik-Cameras.de but I have been unable to find a record of the auction.

Apparently Canon did not bid on it showing their doubt about its authenticity. That camera had no markings on it whatsoever except for the numeral 2 stamped in the baseplate. We just don’t know the origins of this camera. However, it may be the one illustrated in the advertisement from Asahi Camera in 1934. I have reproduced some of images from that report here. Was this a Kwanon-D? Someone paid a lot of money assuming it was.

Three images of the camera referred to in the Klassik-Camera.de article Presumably these are from the auction catalogue. With the exception of the collapsible viewfinder this camera appears identical to the one in the ad pictured above on the left. It could be authentic or it could be a forgery. One would want to examine it in person including some disassembly to form a valid opinion.

This image of a Kasyapa lens is taken from the Klassic-Camera article. It appears identical to the lens on the Kwanon-X at the top of the page.

Now, to change the subject, the lens(es) on the Kwanon(s) are also an enigma. They appear to be M39 screw mount 50mm f/3.5 collapsible lenses called the “Kasyapa” after Mahakasyapa , a disciple of the Buddha. They look very like the Leica Elmar of the same 50mm f/3.5 configuration but the source of these lenses is unknown. I have found no other information on them. As I say, another enigma.

In the fall of 1934 Yoshida left Seiki Kogaku. The Canon Museum says of this that the “..approach taken by the laboratory in producing cameras was no longer consistent with what he wanted to do”. I think that probably Japanese decorum has allowed no further comment on this unfortunate turn of events. We don’t know the real story other than Yoshida drops out of the Canon saga not to reappear.

Work continued on the Kwanon but events overtook and delayed its development. The first problem was the development of the Kodak 35mm film canister in the US in 1934. Kwanon had been developed for two light tight canisters with the film travelling between them. There was no need to rewind the film. The Kodak canister required a means of rewinding the film into the single canister. This called for modifications to the body to accommodate it.

The second was the development of the pop-up viewfinder developed by Tomitaru Kaneko which offered a much improved viewing experience and required more changes to the camera body.

The Kwanon’s had a Leica M39 thread lens mount but Leica had patents on this mount and the rangefinder coupling method which exposed Seiki-Kogaku to law suits if the cameras were to be marketed commercially. A different mount and rangefinder coupling had to be found.

Finally, there was the name. It was felt that the overtly religious connection may present a marketing problem and a more neutral brand name would be easier to sell. “Canon” was arrived at as the new name because it was pronounced the same as Kwanon in Japanese and because in English it could mean an authority or standard.

In June of 1935 a copyright application for the name Canon was filed and the trademark was granted in September. The first ad for a Canon camera appeared in the October 1935 issue of Asahi Camera magazine.

And so the first camera that was to be brought to market was to be called “Canon”. But troubles lay ahead for the young company; troubles that almost destroy it before it can firmly establish itself.

This website is the work of R. Flynn Marr who is solely responsible for its contents which are subject to his claim of copyright. User Manuals, Brochures and Advertising Materials of Canon and other manufacturers available on this site are subject to the copyright claims and are the property of Canon and other manufacturers and they are offered here for personal use only.