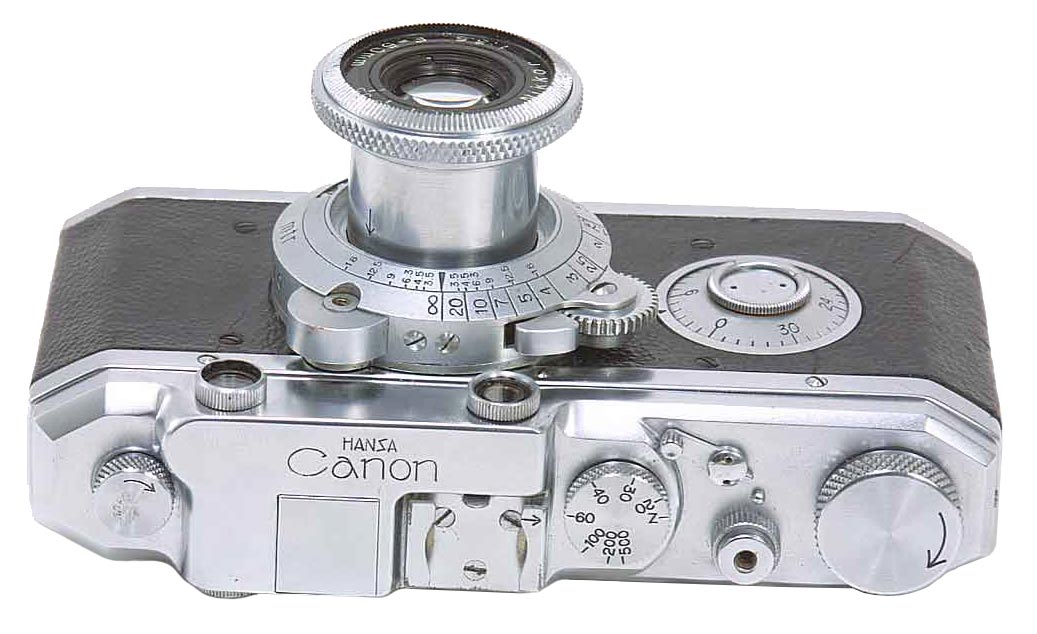

The commercial version of the Kwanon, the Hansa Canon. (Photo is from Pacific Rim Camera)

The War Years

Canon’s history has been one of evolution; of taking what they had created and making it better. The idea for the first Canon 35mm camera had culminated in the Kwanon. But in June of 1935 when Seiki Kogaku applied for a trade mark of the name “Canon”, thinking had gone beyond the Kwanon. It was not to be abandoned. It was to evolve.

We don’t know where the lenses for the Kwanons, the Kasapya lenses, came from. Likely they were purchased and rebranded. At most it appears that only

ten were created/acquired. But if a production camera was to be manufactured in any numbers, it had to have lenses and in the late 1930’s Seiki Kogaku did not have the resources to create them. They needed to source a reliable supply of appropriate optics: lenses, viewfinders and rangefinders.

The “Hansa” on the Hansa Canon indicates that this camera was sold by Omiya Shashin Yohin Co. Ltd. (Omiya Camera & Accessory Shop). (Photo is from Pacific Rim Camera).

The cap in the middle of the back can be removed. There is a corresponding hole in the pressure plate and the focus can be adjusted by looking at the image the lens makes. (Photo is from Pacific Rim Camera)

Saburo Uchida’s brother, Tyonosuke Uchida, was once an auditor for Nippon Kogaku Kogyo (Japan Optical Industries Inc.) which was the largest optical manufacturer in Japan at the time and was the company that eventually became Nikon. It was founded in 1917 and was jointly owned by the Imperial Navy and Mitsubishi Trust. This large optical company was heavily invested in military production for the Japanese war industry.

Tyonosuke was able to get his brother an introduction to Toyotaro Hori, an executive VP at Nippon Kogaku who at the time was looking into non-military product feasibility. He was interested in a commercial application for their Nikkor lenses.

With the lens out of the focus mechanism the unit can

be examined. That unit itself screws out of the J Flange

on the camera. (Photo is from Pacific Rim Camera)

An agreement was reached that the two companies would co-operate in the production of a 35 mm camera with a Nikkor f/3.5 50mm lens. The arrangement was not a simple purchase of lenses but rather a joint venture with Nippon Kogaku having considerable say in the development of a commercial camera including the appointment of a factory manager.

The first Canon under this arrangement came to market in February of 1936 (Dechert says the production began around October 1935 but production records from the war years and before are lost so all such information is based on estimates). Nippon Kogaku was responsible for the lens, the rangefinder optics, and the optical mountings. Seiki Kogaku was responsible for the body of the camera including the focal plane shutter and the overall assembly.

The Hansa Canon, as it came to be called, had a threaded lens mount flange, the “J Flange”, into which screwed a wheel operated focusing mechanism. The lens was a bayonet design that mounted into the focusing mechanism. This device was designed by Nippon Kogaku

and it avoided infringement of Leica and Contax patents. The diameter and thread pitch of the mounting flange were different enough that M39 lens could not fit.

The rangefinder was a self contained unit assembled by Nippon Kogaku that could be mounted on the camera bodies as delivered.

When this first commercial camera was released Seiki Kogaku had no sales channels so the company approached Omiya Shashin Yohin Co. Ltd. (Omiya Camera & Accessory Shop) about marketing the new camera. Omiya had a trade name “Hansa” as their trademark and they agreed to market the cameras but cameras they sold would have that trademark included on the top plate. And so Canon’s first commercial camera was called the “Hansa Canon” and it is so known by collectors to this day. Most of these cameras were sold by Omiya but those Canon sold directly did not have “Hansa” engraved on the top deck.

An advance announcement article for the Hansa Canon appeared in the October 1935 issue of Asahi Camera. In that article it was clearly stated that this camera was based on the Leica design. The Canon Museum quotes from the article, translated to English of course:

“Hansa Canon camera …. Canon is a Leica imitation made in Japan. Although some influence of Contax is found, the majority of its features are modeled after the Leica. …. It uses a special magazine and the lens is Nippon Kogaku’s Nikkor 50mm f/3.5. The lens is removable. …”

The Hansa Canon was Japan’s first quality 35mm rangefinder camera and it was recognized as such. Production was from approximately October 1935 to around June 1940 and Dechert estimates that 1,100 were made.

Canon Model S

(Canon Newest Model) is mostly a Hansa

Canon with slow speeds, the frame counter move to the top deck

and a changed top deck layout. (Canon Museum Photograph)

Notice the determination of these early developers of Canon. They had to have lenses and to get them they allowed some control of production to slip from their hands. But ten years later they were making their own lenses and had control back in their own hands. They had no sales channels and they allowed another company to have their name on the cameras. But by the end of the war this practice had stopped. These men were determined and creative in pursuing their goal of viable camera production. And this drive exhibited so early explains why Canon is the company it is today. However, back to our story.

In June of 1936 “Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory” changed its name to “Japan Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory” and they moved into improved facilities now that they were actually producing cameras.

The control exercised by Nippon Kogaku must have rankled the men Seiki Kogaku and by mid 1937 they were talking about

producing their own lenses. Yoshizo Furukawa, the companies first optical engineer, began work designing lenses in the late 1930’s, even before they had the ability to make them. A contest was held within the company for a name for the original 50mm f/3.5 and 135m f/4 lenses that were planned and “Serenar” was chosen. In December of 1941 Seiki Kogaku applied for trademark protection of the terms “Serenar” and “Serenon”.

Camera production proved difficult and slow, between 5 and 10 per month initially. They were short of cash, staff and parts. To raise cash it was decided to incorporate a joint stock company making it easier to attract investors. On the 10th of August 1937 they created “Precision Optical Industry Co. Ltd.” To this day Canon considers this to be the date of the founding of the Company.

This move loosened up some cash and production began to improve but it was still totally by hand.

Canon Model J

(marketed as the Popular Model) introduced in

1939 was a basic economy model with no rangefinder or slow speeds. (Canon Museum Photograph)

Improvements to the basic design went on continually. In October of 1938 Seiki Kogaku began production of Canon S or the “Newest Model”. Production of this model continued thru the war years to 1945 with about 1,600 being made. Essentially this was a Hansa Canon with slow speeds controlled by a dial on the front of the camera.

After the Model S Canon came out with the Canon J almost immediately. This was a simple basic camera. First sold as the “Popular Model” it came to be known as the Model J. Canon has always created top line cameras and then brought out the same model with fewer features and a lower price point for those who could not afford the more expensive model.

The Model J had no rangefinder, only a viewfinder and the slow speeds were eliminated. The lens screwed directly into the J flange and focusing was done using the distance scale on the lens body. Dechert’s best estimate of number produced was 200 and that production stopped in 1941.

Kitchingman says early in 1939 Seiki Kogaku acquired two lens generators, five lens polishing machines and a lens checker device. A technician from Nippon Kogaku came to Canon to set up these machines and train staff. He apparently stayed on to assist in designing new lenses.

About January of 1940 Seiki Kogaku introduced the Canon NS as a replacement for the Hansa Canon. In advertisements of the time it was called the Canon “New Standard Model without slow speeds” but collectors have called it the “NS”. Made until 1942 about 100 were produced. Identical to Canon S without slow speeds.

The Canon NS or “New Standard” model was essentially a Canon S with no slow speeds. (Canon Museum Photo)

The Canon JS is a Canon Model J with slow speeds however records for this camera are sketchy at best. (Canon Museum Photo)

The Canon Museum says that the NS was designed with no slow speeds to get the cost of their camera down to compensate for a government tax to raise money for the war effort of between 10 and 20 percent.

1941 saw the introduction of the Canon JS which was simply a Canon J with slow speeds. Made till about 1945 Dechert estimates the number made at no more than 50. However it appears that information on this camera is very uncertain. The Canon Museum suggests these were intended for closeup or other special application photography. Dechert suggests they may have been a special order for the Japanese army for use as copy cameras. But nothing about the origins of this camera is certain.

That briefly summarizes camera production of Canon cameras during the war. But something that histories of Canon seldom discuss was the war itself, the elephant in the room. For Japan the war did not begin in 1941 but in 1931 with the invasion of Manchuria and continued against China 1937. By 1941 Japan had been at war constantly for 10 years. Although there had been no war damage inflicted on the home islands the society had been on a war footing at home and the demands of the military war machine were everywhere. Since the early 1930’s the military and the governmental bureaucracy argued for a “total war” footing for Japanese industry and society. This attitude actually had a name: the “1940 System.”

Seiki Kogaku was a new enterprise and really had no significant output that would interest the military initially. Normal society did carry on and they were certain that enough citizens, even in a war economy, would be able to buy cameras to make their efforts worthwhile.

As the war progressed and the company began to produce cameras many were acquired by the armed forces. Initial lenses were not sold commercially but to the government and the military. By the time the war in the Pacific began in earnest in 1941 almost all production was directed to the war effort. The lenses were mainly directed towards enlargers and X-ray machines. One can see the decline in camera production as the war progressed and especially after the American bombing of the major cities began.

Canon made X-ray camera protoptypes for the Imperial Navy during 1939-40 using 35mm cameras bases on the Model J. By late 1940 production of a standard model x-ray camera had begun. Wartime production ended in 1944 but after the war in January of 1946 design and production of X-ray cameras resumed under the Seiki Kogaku name.

Doctor Takeshi Mitarai who became a driving force at Canon is often referred to as the “father” of the Canon camera. (Photo courtesy of Wallace Litwin)

Takeshi Mitarai was a friend of Saburo Uchida. He was an obstetrician by profession and had actually established the Mitarai Obstetrics and Gynaecology Hospital in Mejiro Ward of Tokyo after working in the obstetrics department of a major hospital. He had been interested in Uchida’s camera company and had actually invested in it. For a while he had even acted as an auditor for the company.

Dr. Mitarai was very interested in Seiki Kogagu’s development of X-ray cameras. These were simply an apparatus for taking photographs of the fluorescent screen of chest and lung X-rays. Direct X-ray photos were difficult and expensive and Seiki Kogaku was looking for a cheaper alternative.

He became more and more active in the company and finally in 1942 was appointed as president. He was to guide the company through the remainder of the war and the post war recovery period and was to be president until 1974.

In February 1944 Dechert says that Mitarai was instrumental in Seiki Kogaku’s acquisition of Daiwa Kogaku, a lens manufacturer engaged in military work. (The Canon Museum refers to a merger in 1944 with Yamato Kogaku Seisakusho [Yamato Optical Manufacturing Co. Ltd.]). I don’t know if this is the same company or a different one.) Before the acquisition of Daiwa Kogaku there is no record of a truly independent optical production facility.

As the war ground Japan down production slowly went from little to none. Sixty six of Japan’s major cities hade been reduced to rubble, an average of 40% of all buildings destroyed, 60% in Tokyo, 5 of Tokyo’s 7 million residents had left the city. Staff, money, raw materials were impossible to come by. When the Emperor finally spoke to the public by radio on August 15th informing them that there was no use in continuing the war Japan was in a state of collapse. And they had to face the uncertainty of the coming American occupation.

Note: This is a most incomplete description of the early years at Canon. My reading to this point has not found much more than this. However, there is a story here and it seems to be an epic tale of perseverance in the face of great adversity. If it has not been told in greater detail somewhere I am sure it deserves to be.

This website is the work of R. Flynn Marr who is solely responsible for its contents which are subject to his claim of copyright. User Manuals, Brochures and Advertising Materials of Canon and other manufacturers available on this site are subject to the copyright claims and are the property of Canon and other manufacturers and they are offered here for personal use only.