The Industry

The rise of the Japanese Camera Industry

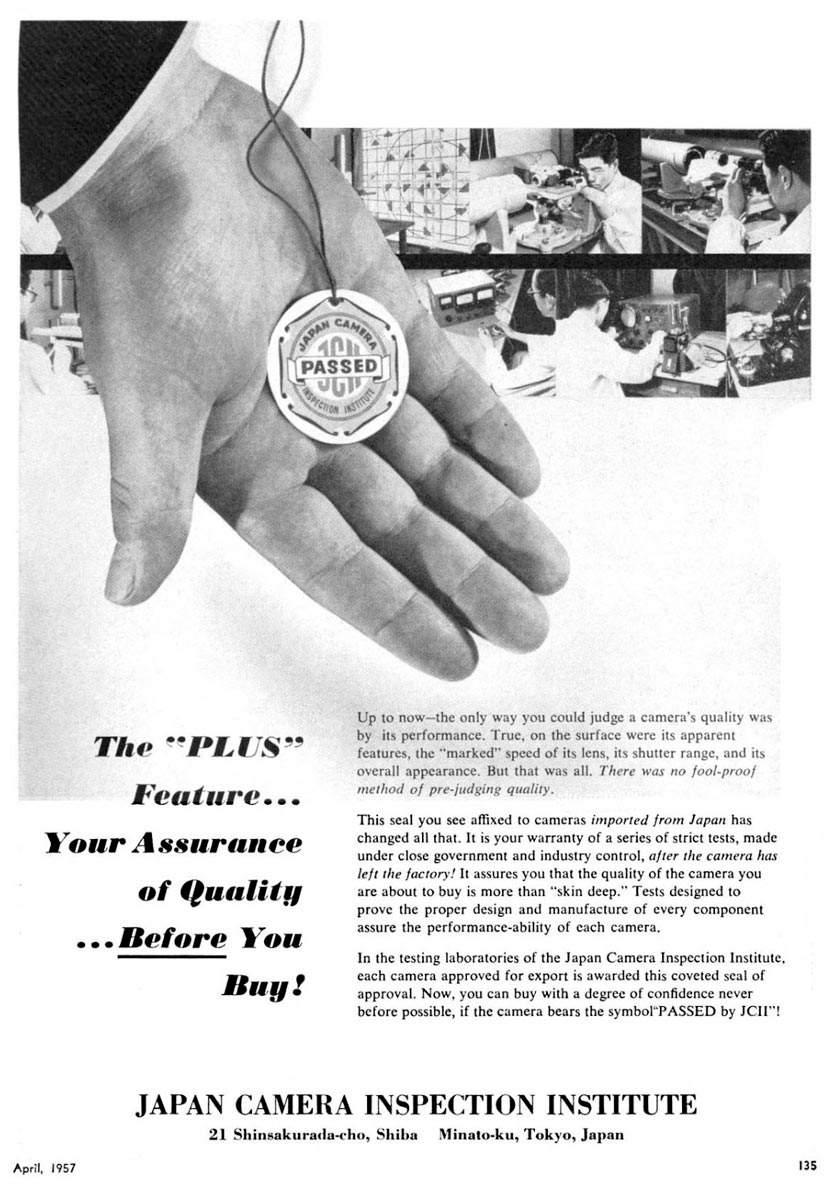

The JCII Medallion attached to all camera products approved for the export market.

The April 1957 issue of Popular Photography had a feature section on the Janpanese camera industry. The image above is an ad for the JCII, the authors of those little gold stickers you find on older Japanese cameras that say “Passed”

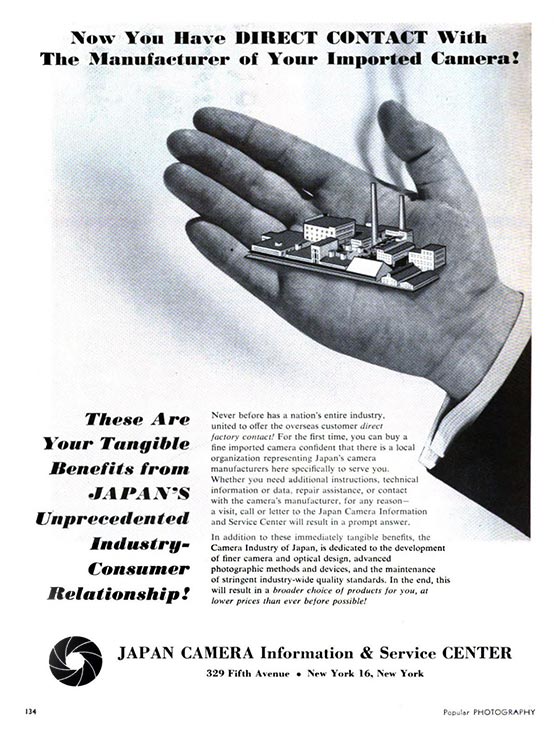

From the same issue of Popular Photography is this ad for the Japan Camera Information & Service Center in New York.

We cannot examine the Canon company and hope to understand it without knowing something of the milieu into which it was born and grew to maturity.

Japan was not late into the camera business. The first industrial lens production facility was opened in Japan in 1907. Like in other nations, the First World War brought on a rapid growth in the optical industry through a military hungry for optical products of all kinds.

July 25th, 1917, one of the great names in Japanese camera history was founded: Nippon Kogaku Kogyo Kabushikigaisha (Japan Optical Industries Co. Ltd.). This company was formed to design and produce lenses for a wide variety of equipment and devices. It eventually slid into the manufacturing of cameras having supplied lenses to several camera manufacturers, including Canon, and in 1988 it finally changed the corporate name to the name its cameras were known by: the Nikon Corporation.

In 1928 another company was founded, this time in Osaka, under the name Nichi-Doku Shashinki Shoten (Japanese-German Camera Shop”. They began manufacting cameras and in 1933 began using the name Minolta on them. In 1937 they changed their name to Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko K.K. (Chiyoda Optics and Fine Engineering Ltd.). Eventually they too changed the company name to that appearing on their cameras.

And there were other startups. In 1903 Konishiroku Photo Industrial Company brought out the “Cherry” Camera. This was the first camera to carry the “Made in Japan” label. This company eventually matured and carried on into the modern era under the name Konica. Olympus was founded in 1919. That was the same year Asahi Optical Company was created. Initially a lens manufacturer it wasn’t till much later that they turned their hand to cameras.

And these few examples are only some of the dozens of firms that were making lenses and cameras before World War II. You can see that when Goro Yoshida started examining his Leica Model II there was already established a long standing and vibrant optical industry in Japan.

In the 1930’s and ’40’s and especially immediately after the war, the average Japanese could not afford a German camera if one was available at all. They were expensive. German cameras were considered the finest in the world and with this reputation came demand and high prices.

What the Japanese could afford were cheap cameras with simple lenses, poor or no focusing ability and primitive shutters. In complexity they were to Japan what the Brownie box camera was to the United States.

Before the second war these were exported to the United States in great numbers where they could be had for as little as a dollar. But they did not fare well against the equivalent Kodak products and they helped to fuel the impression that the Japanese were unable to make precision equipment.

This was the world that the forerunner of Canon Inc. was born into. From its inception the company was dedicated to the manufacture not of lenses but of cameras making it somewhat unique as a start up. Not only just cameras but Goro Yoshida and his associates wanted to build quality cameras at a reasonable price for the home market. Dreams of international dominance were still years away. But 1933 was not an auspicious time to be creating a new business in Japan. War was coming and it was to be a mixed blessing.

As in all countries embroiled in the Second World War, home industry in Japan was devoted to military production. In a way it was good. There was money for research and development and a workforce was trained in the optical industries. But it was also bad. The war brought death and destruction and commercial chaos. It was so difficult after the end of the war that the folks at Canon almost threw in the towel. Although the early Canon company was not seriously damaged during the war, materials were hard to come by, machinery and equipment almost impossible to maintain and repair, and the workforce was in chaos. For several months all they could do was turn out a few cameras from parts they had in store.

So here is what Canon faced: the country was defeated in war and laid waste, it was occupied by the American army, the world economy was a mess, and there was strong racial prejudice where the Japanese were concerned, and the perception was that their manufactured goods were inferior. The whole of the Japanese camera industry faced this rather bleak picture. So what do you do? Well, I guess you start by building one camera at a time.

Several things seemed to have happened almost simultaneously. The Japanese have a singular ability to act in unison and with purpose. And so it was in this very difficult time. By 1948, three years after the war, the Japanese government had enacted a law regulating the inspection and control of manufactured goods destined for export. This was in reaction to an awareness of the importance for the future of trade exports that Japanese goods be perceived as being of superior quality.

At the same time Canon, and I assume other Japanese camera producers, found a ready market for their cameras in the hundreds of thousands of US servicemen who came through their country as part of the occupying forces. These men found quality cameras and very reasonable prices and they bought them in great numbers. So popular were they that the US Army base PX stores began to stock cameras for the servicemen.

In 1954 the major producers of Japanese cameras, over fourty separate firms, formed the “Japan Camera Industry Association” with a view to shaping the market and making it more favourable to Japanese optical products. The stated objectives were to 1) Investigate market conditions and compile statistics; 2) Liase with Government authorities in industry promotional efforts; and 3) Liase with related organizations at home and overseas to stay in step with international developments in cameras and optics.

If you were an American amateur photographer in the early 1950’s and you were about to spend a couple of hundred dollars, big 1950’s dollars, on a new camera, would you put your money on one from an unfamiliar supplier from a distant land and with whom you had just fought a long war? How would you get it serviced? How would you enforce warranties? Where would spare parts come from? How would it stand up to normal everyday use? These were all important questions and the Japanese camera suppliers knew they were considerations taken into account before the purchase in America of a Japanese camera.

One of the first things that the Association did was open the Japan Camera Information and Service Center at 329 5th Avenue in New York City. This was not a store. It sold nothing to the public. Its purpose was to provide information and service to distributors and the public about all Japanese cameras and photo equipment. It could refer people to qualified repair services and it was a source of spare parts for camea companies that did not have thie own parts depots in the US. The Center also had specialised test equipment and staff engineers to diagnose camera problems. The opening of this store front office was a concrete example in America of the Japanese commitment to the American consumer.

Of course, individual companies opened offices in the US and entered into agreements with well known American companies to market Japanese cameras. Two prominent examples of this are Canon’s deal with Bell & Howell and Asahi’s deal with Honeywell. This was another very effective way to create confidence in Japanese cameras.

While all of this was going on the Japanese government was also involved in the promotion of Japanese products. How much of a role the Japan Camera Industry Association had to do with this I don’t know but probably a great deal.

Under the law passed in 1948 the Government set up the Japan Camera Inspection Institute (“JCII”) with the goal of improving the overall quality of Japanese optical equipment destined for export. The JCII immediately imposed a ban on the export of all toy-like cameras and obvious knock off’s of foreign cameras. And any other camera that was to be exported had to be inspected and approved for export.

A Canon AV-1 with the JCII “Passed” sticker on the side of the pentaprism housing.

Closeup of the JCII “Passed” sticker.

Samples of cameras ready for export had to be submitted for testing by the Institute. The inspectors could not be connected to any of the camera companies. They also had to have University training and at least two years experience inspecting cameras. They travelled to the various plants around the country to inspect the facilities and the cameras to be exported.

Cameras were subjected to an “Appearance” test. Was the finish and fit. Then there was the “Symmetry” test. Were lettering and logos properly positioned? Was the fit of the parts even throughout? And then there were “Function” tests. Did the camera function smoothly? Were settings accurate? Did the camera or lens have the durability required?

Initially cameras approved for export were given a paper medalion to be attached to it. At the top of the page is an image of the medallion and an ad for the JCII from Popular Photography of April 1957. The use of these Seals was short lived and the Institute moved to the Gold Stickers that appear on early SLR’s from Canon.

By the mid 1980’s Japanese cameras had become the world standard and German cameras were in decline. They had been fully accepted by the market. There was no further need for the Japan Camera Center or the JCII. Inspection was discontinued by the end of the 1980’s.

Such was the effectiveness of the JCII program that there were phoney stickers created in an attempt to add value to some cheap or second hand cameras. This may affect some cameras or people but the presence of the sticker in the collector market does not significantly affect value.

This part of the Canon story is an interesting example of how a country and an industry can work together to overcome market chaos and consumer resistance and become the world standard for quality cameras.

This website is the work of R. Flynn Marr who is solely responsible for its contents which are subject to his claim of copyright. User Manuals, Brochures and Advertising Materials of Canon and other manufacturers available on this site are subject to the copyright claims and are the property of Canon and other manufacturers and they are offered here for personal use only.